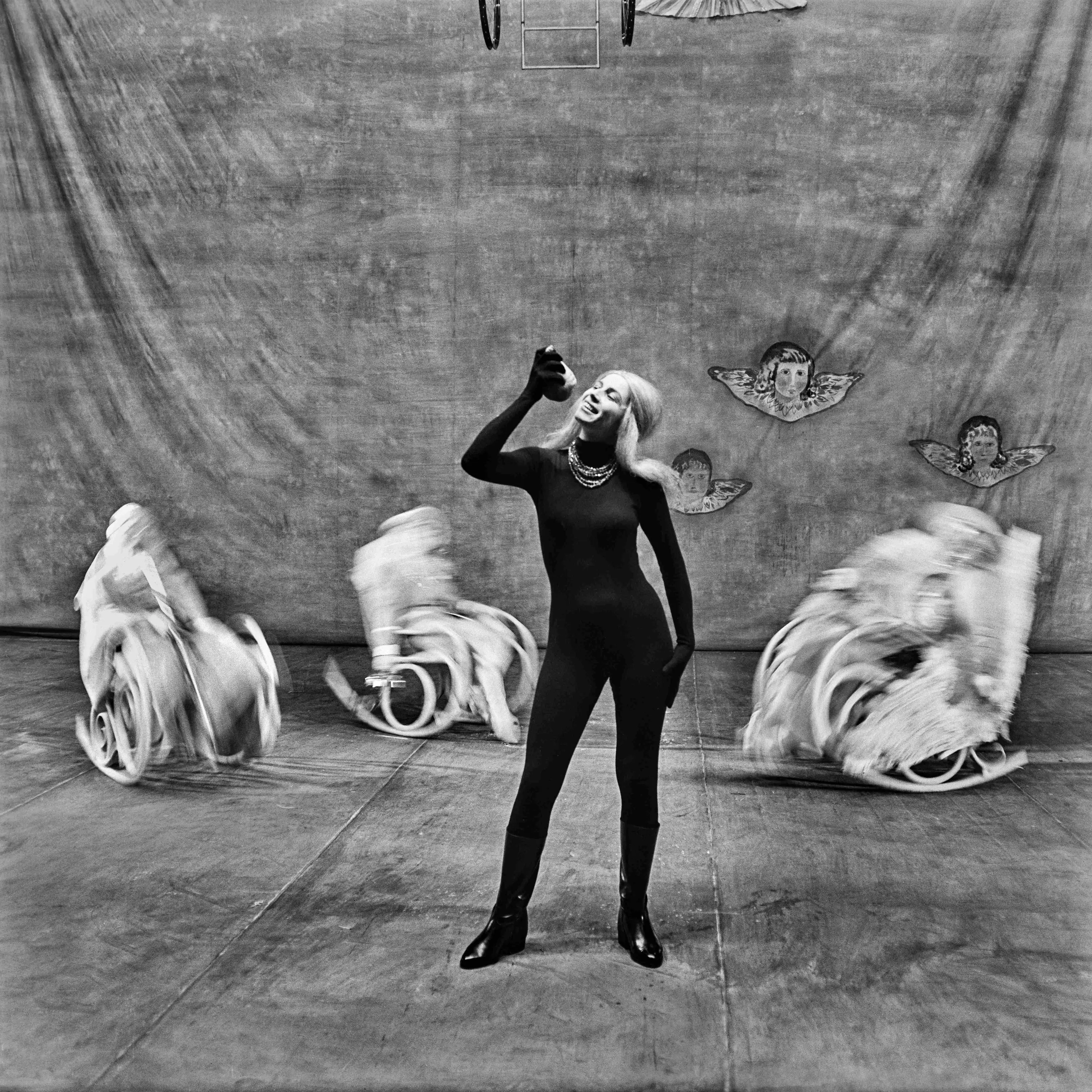

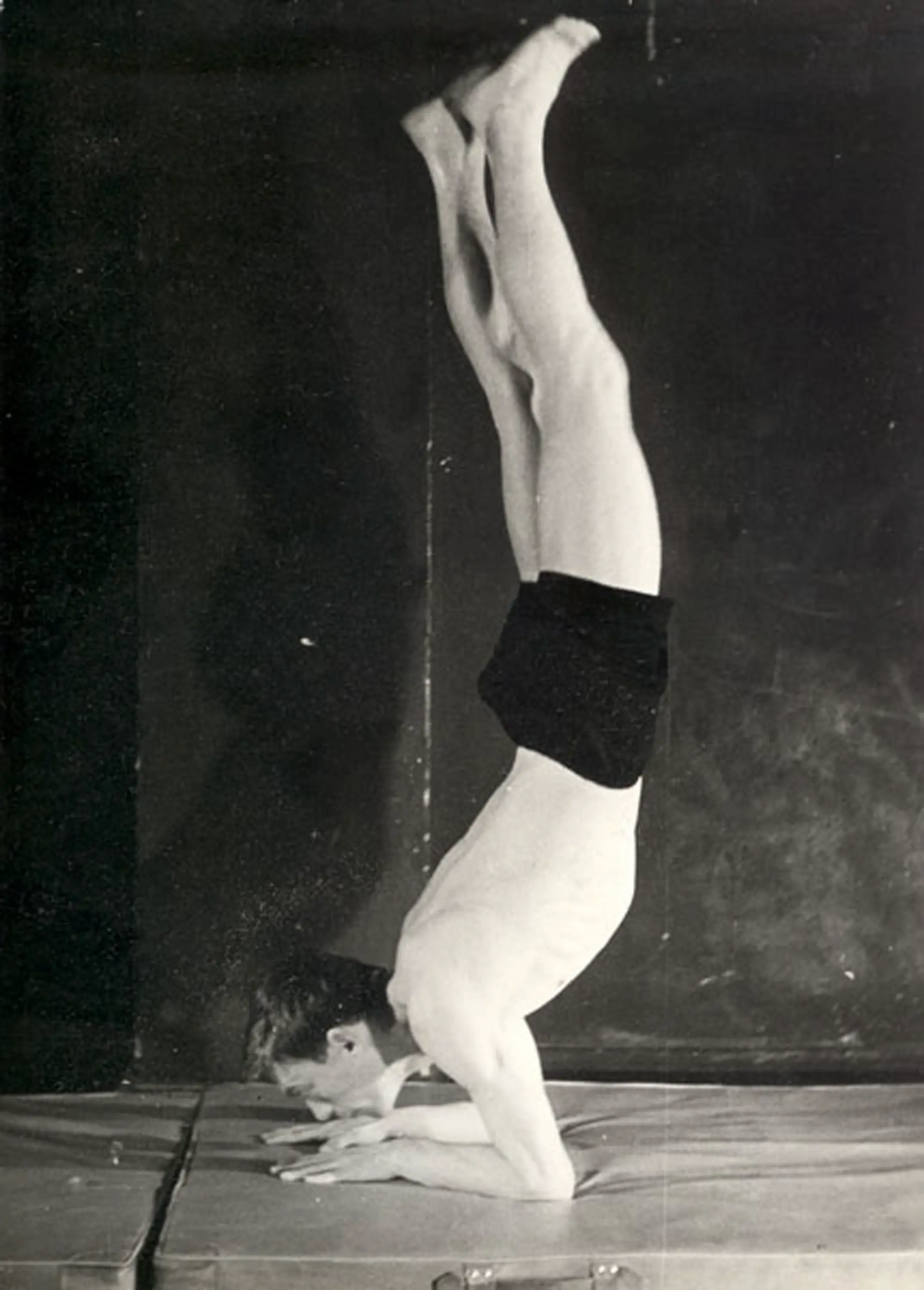

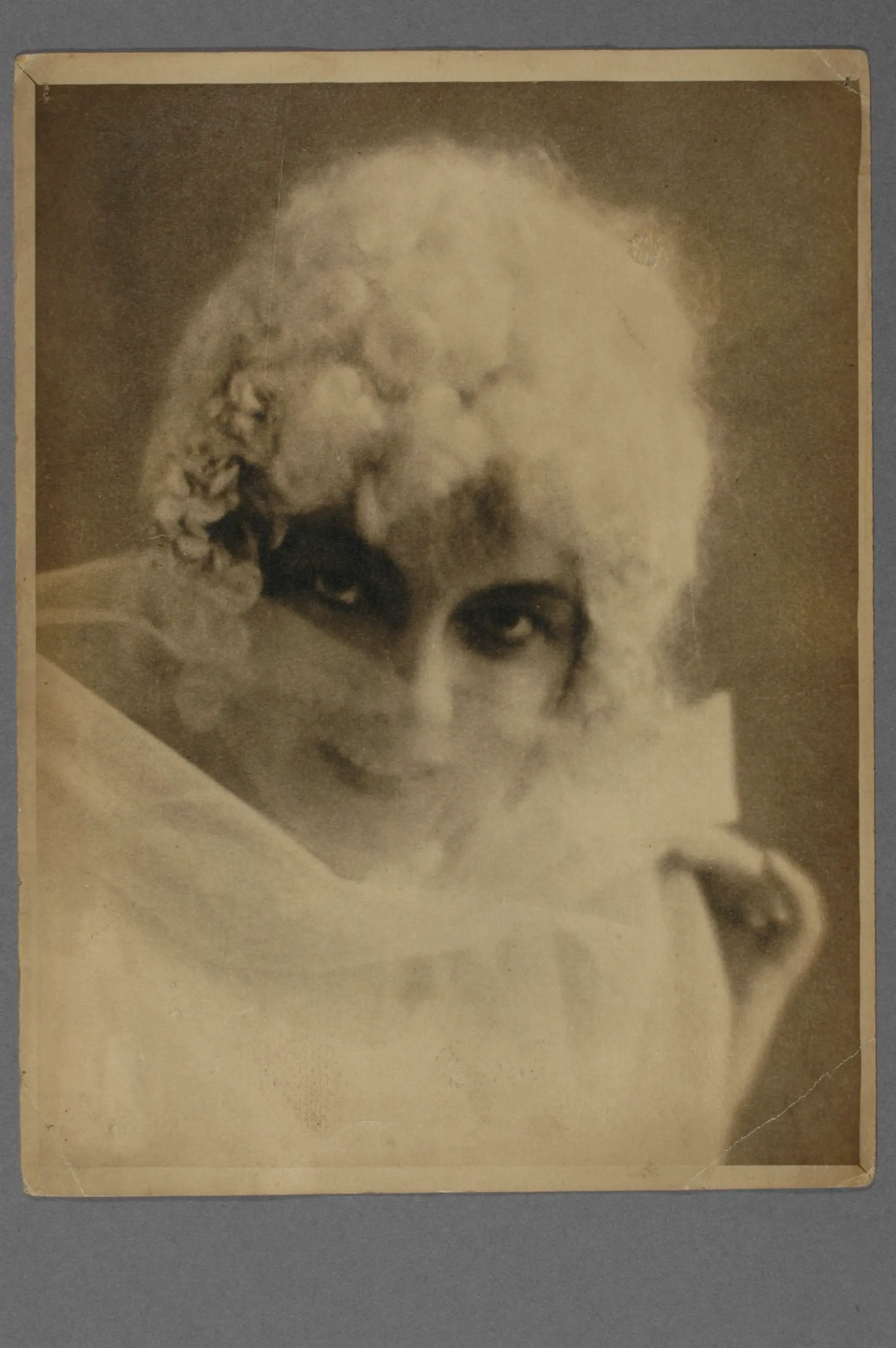

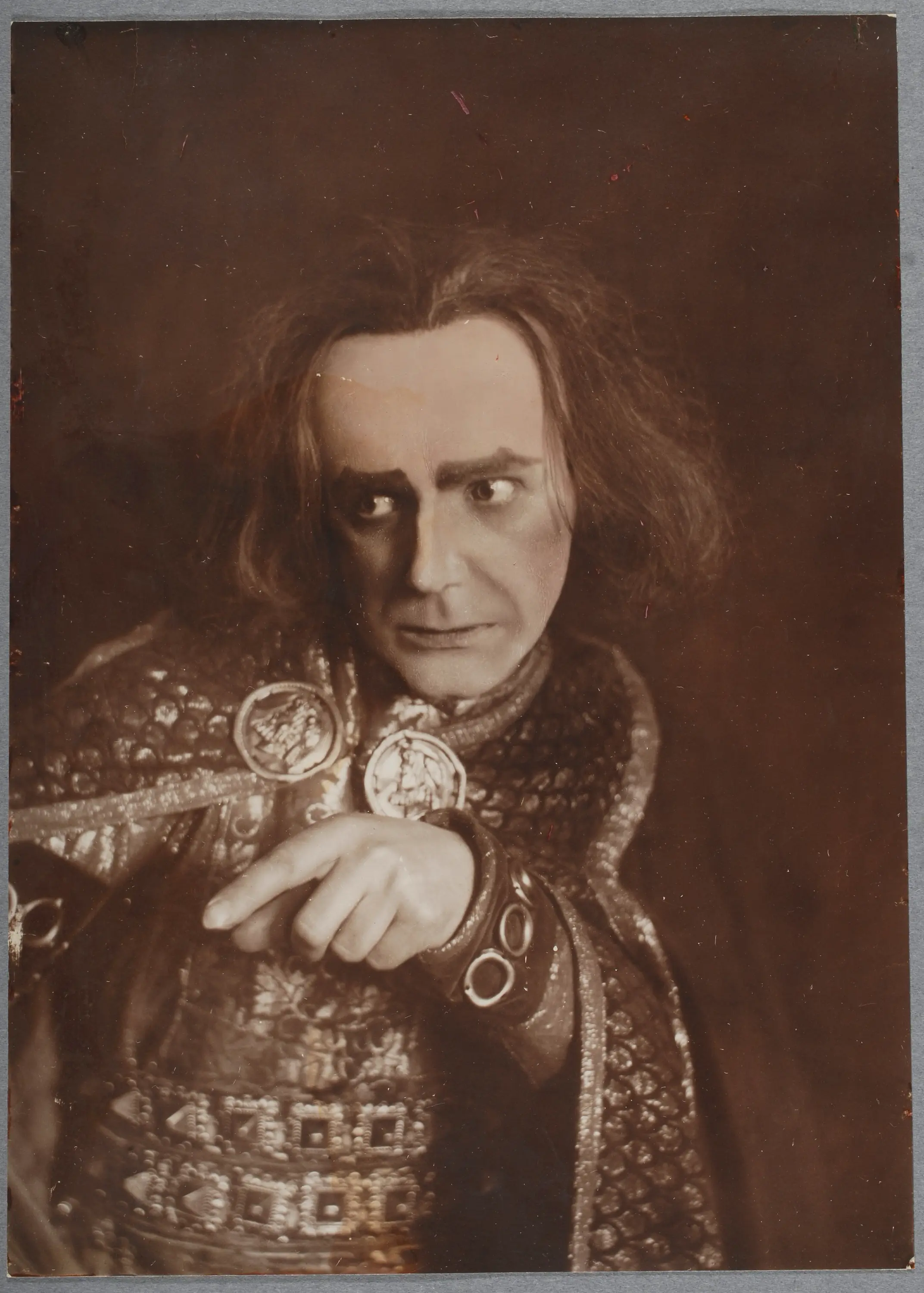

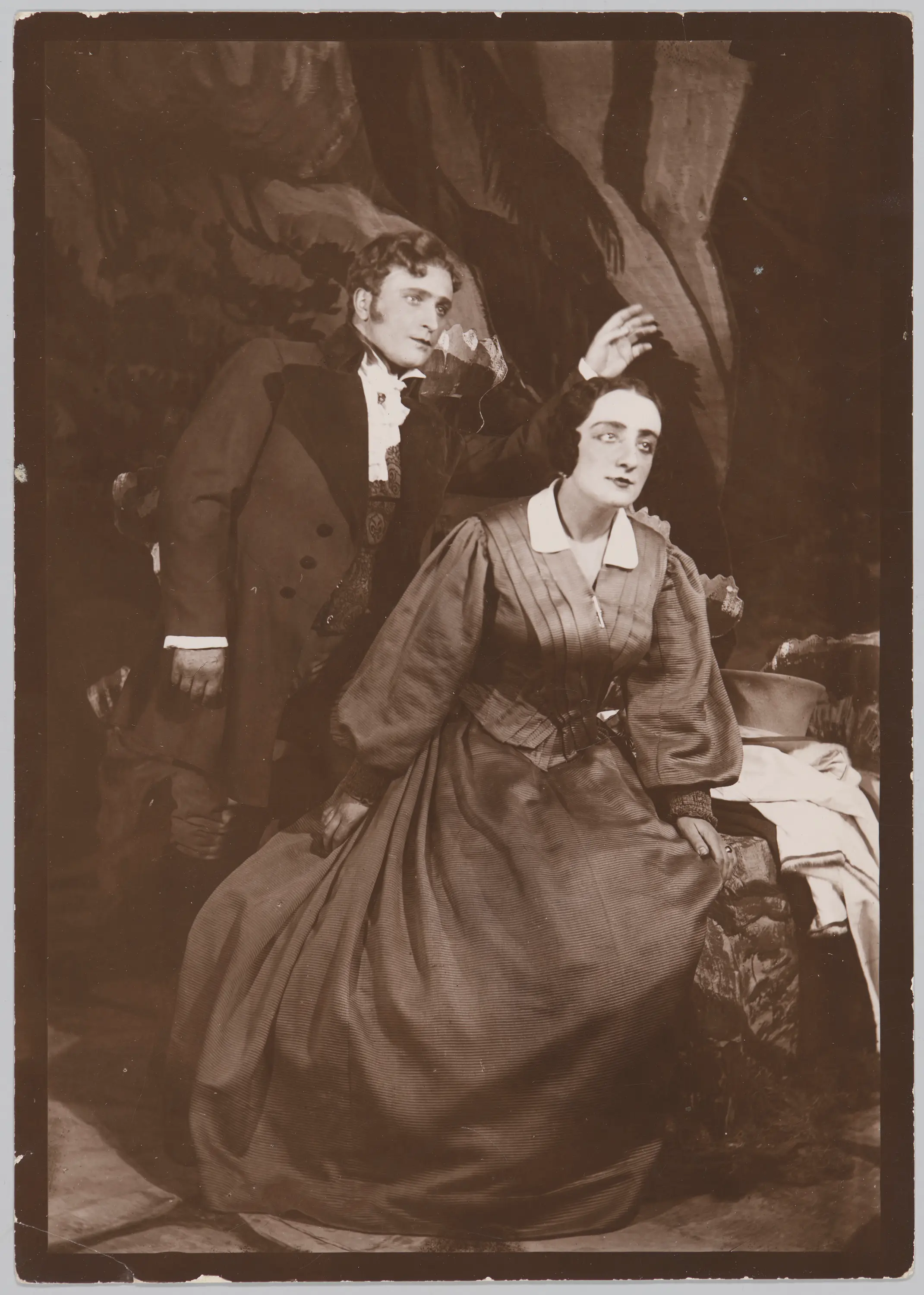

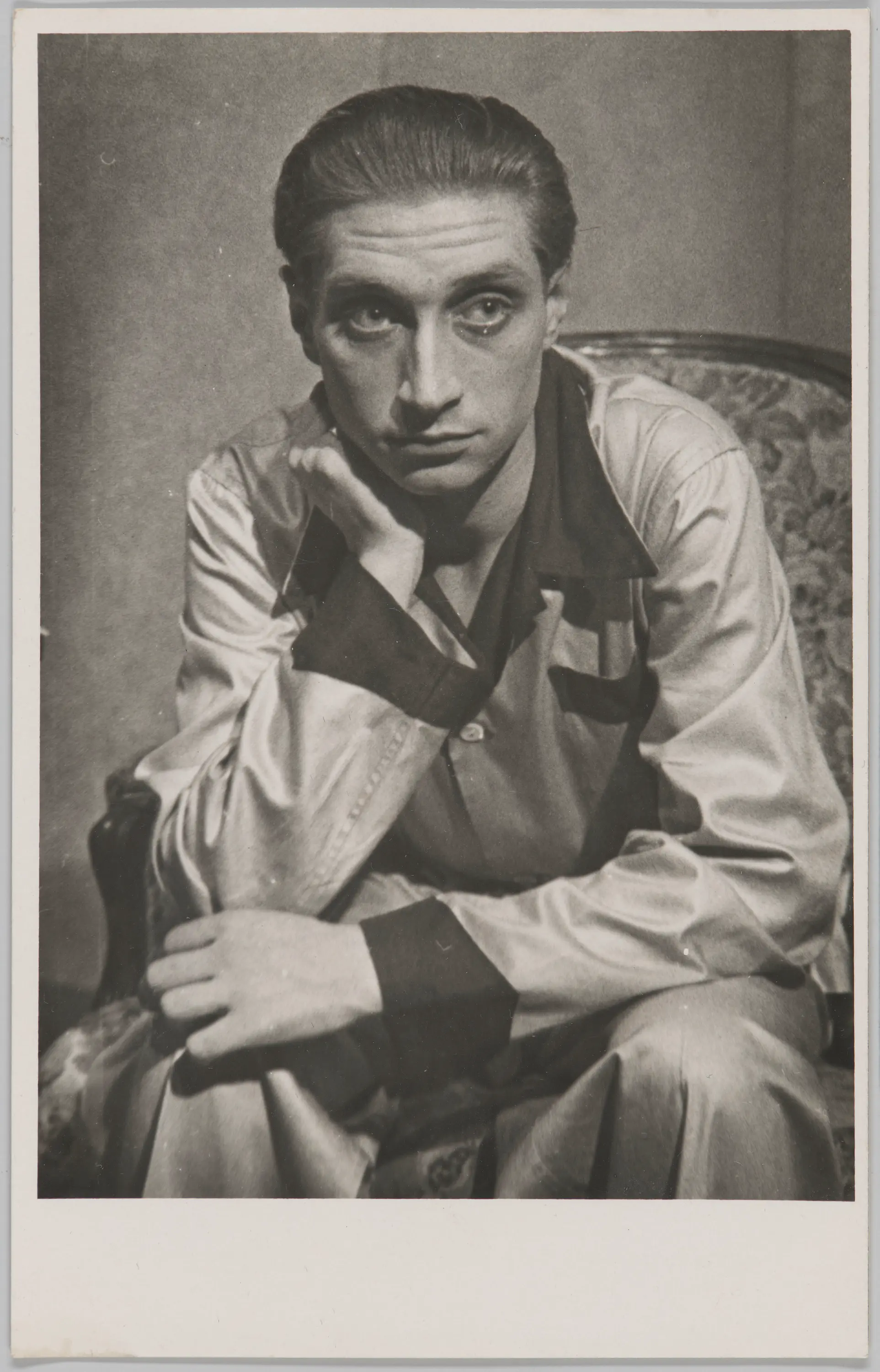

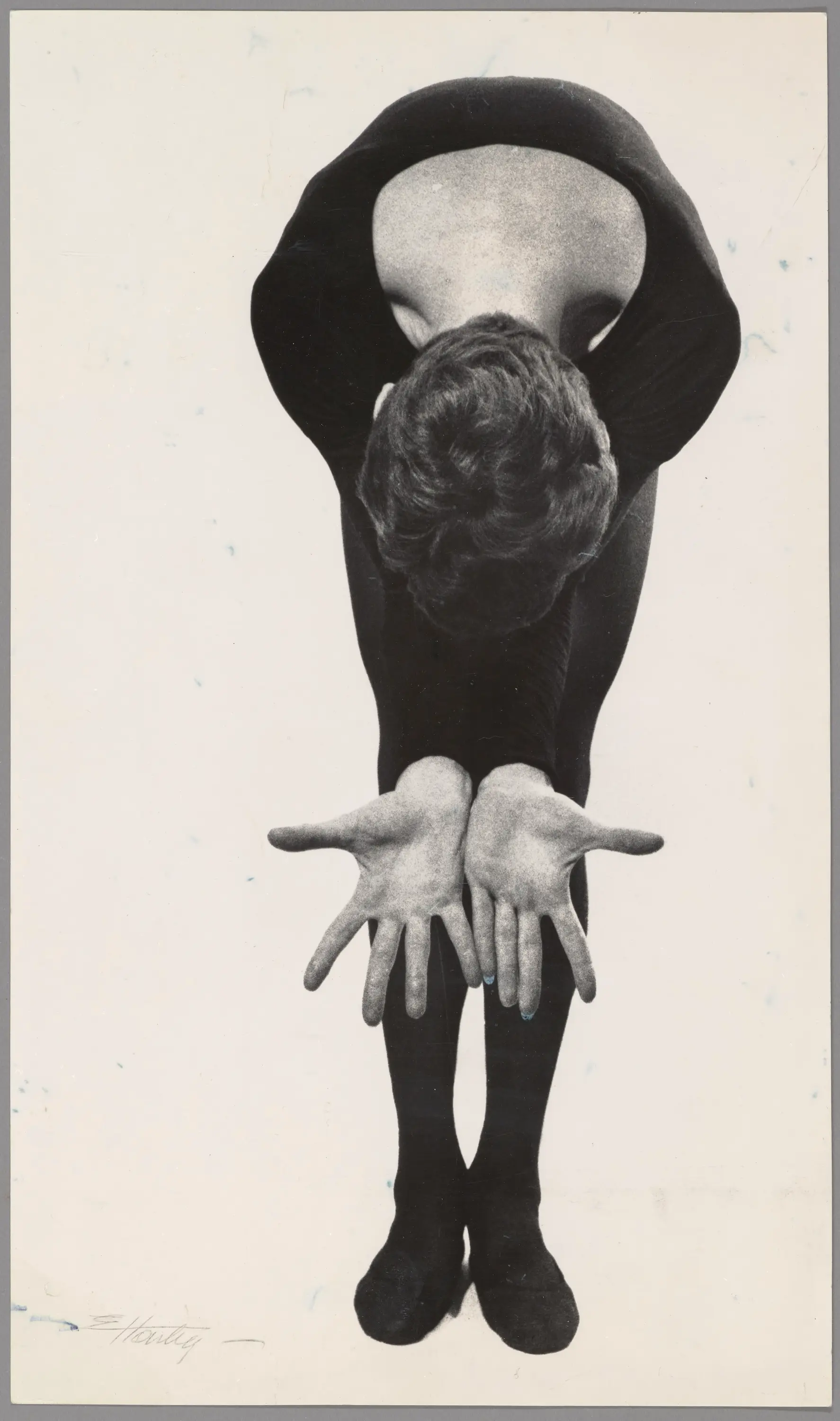

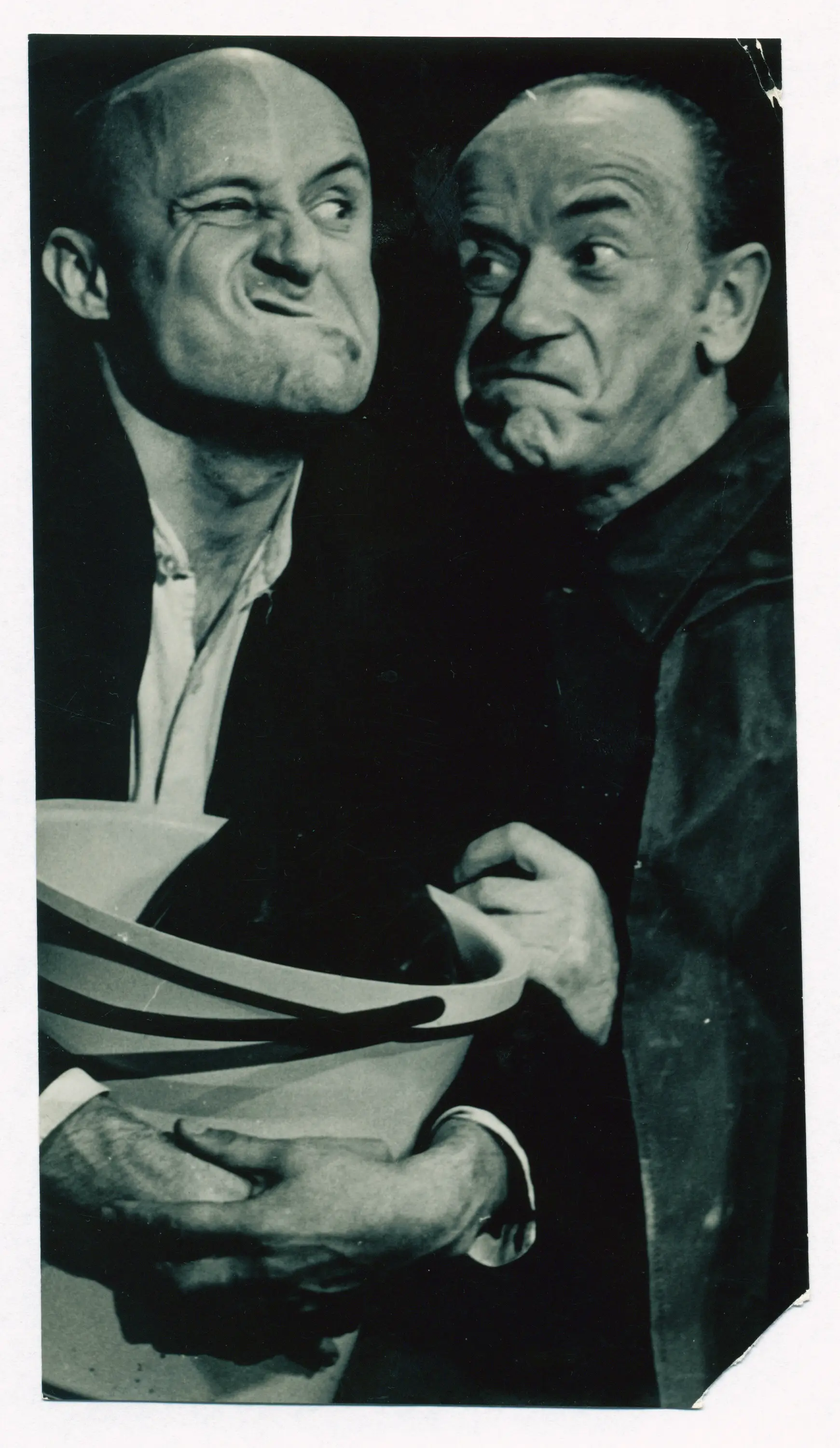

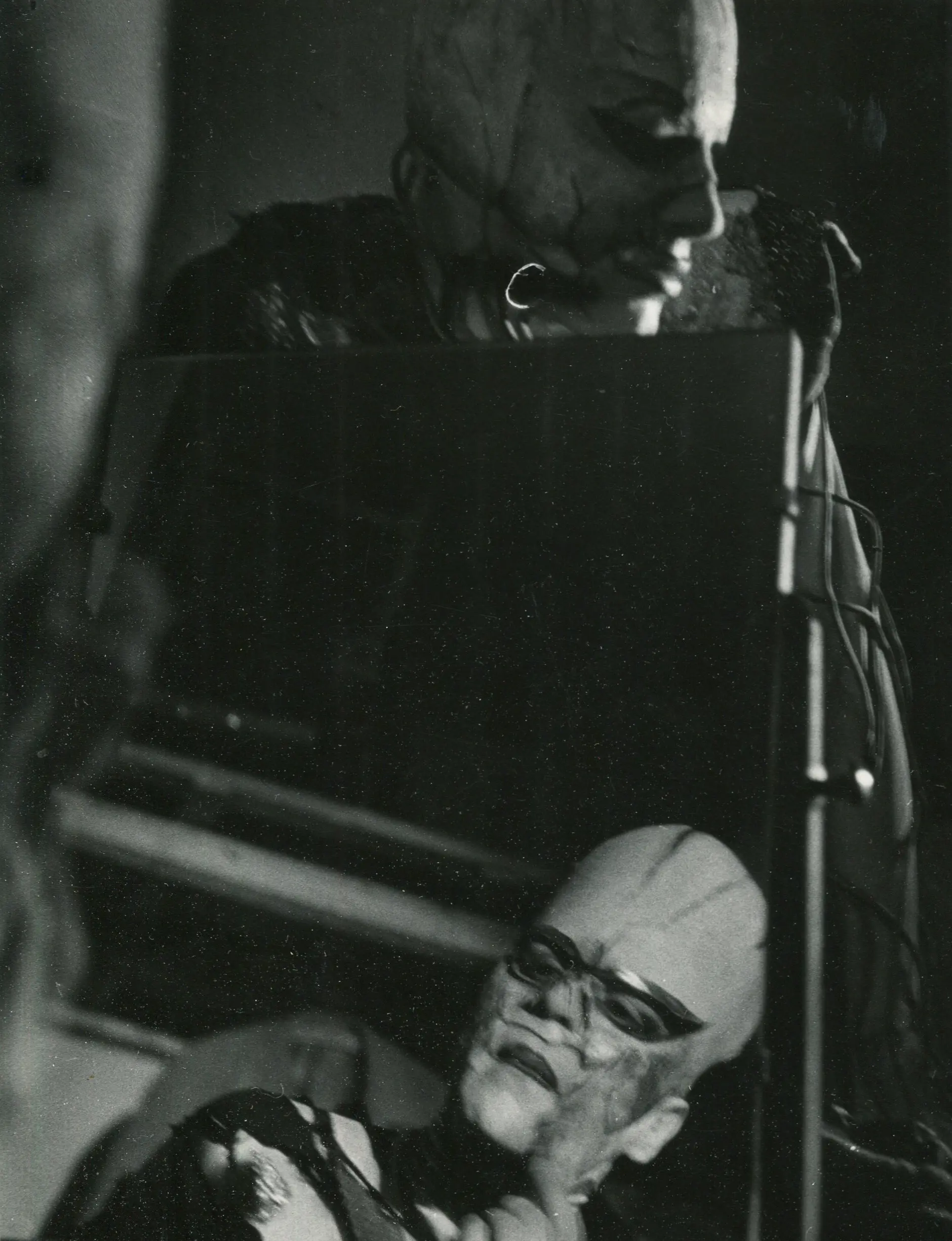

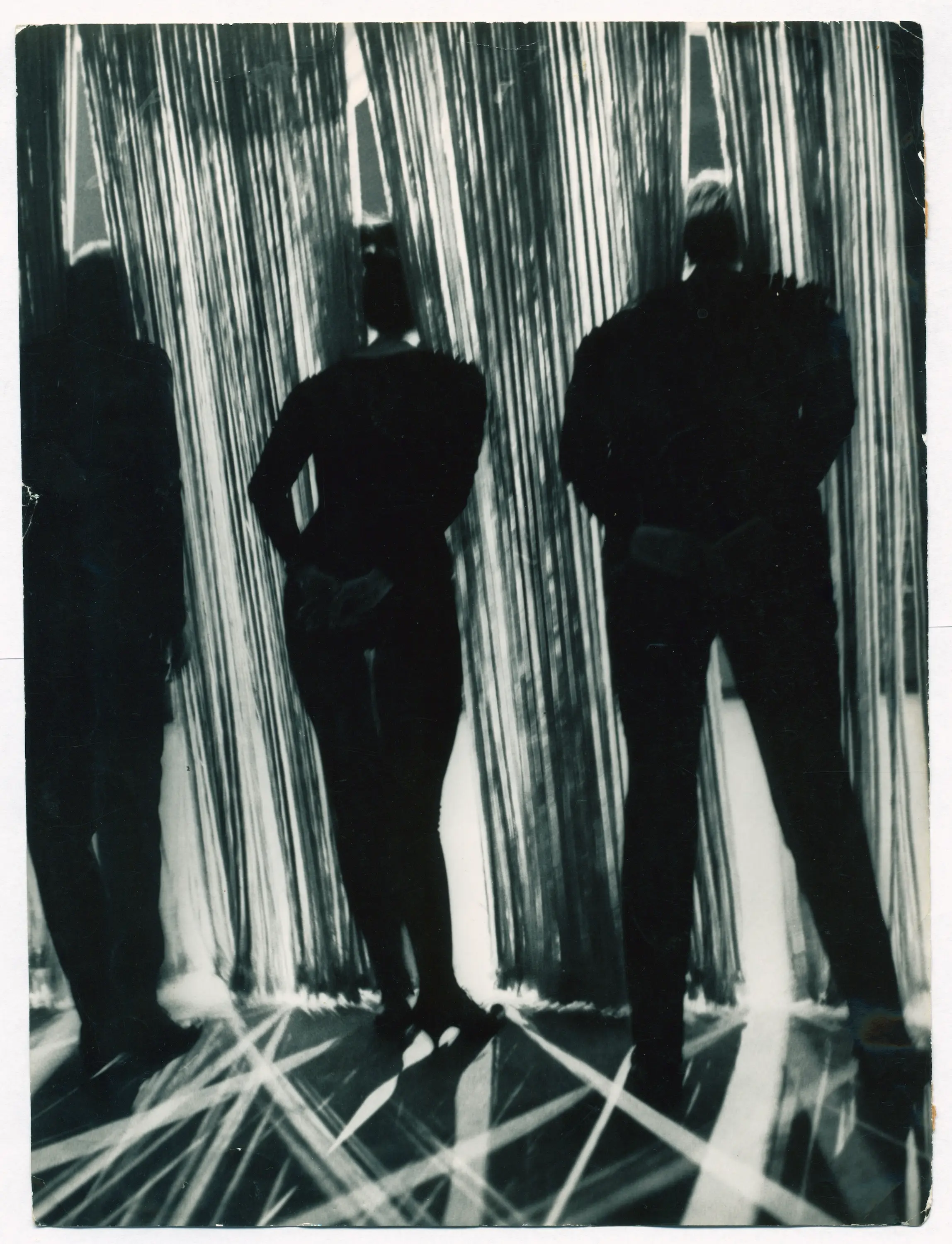

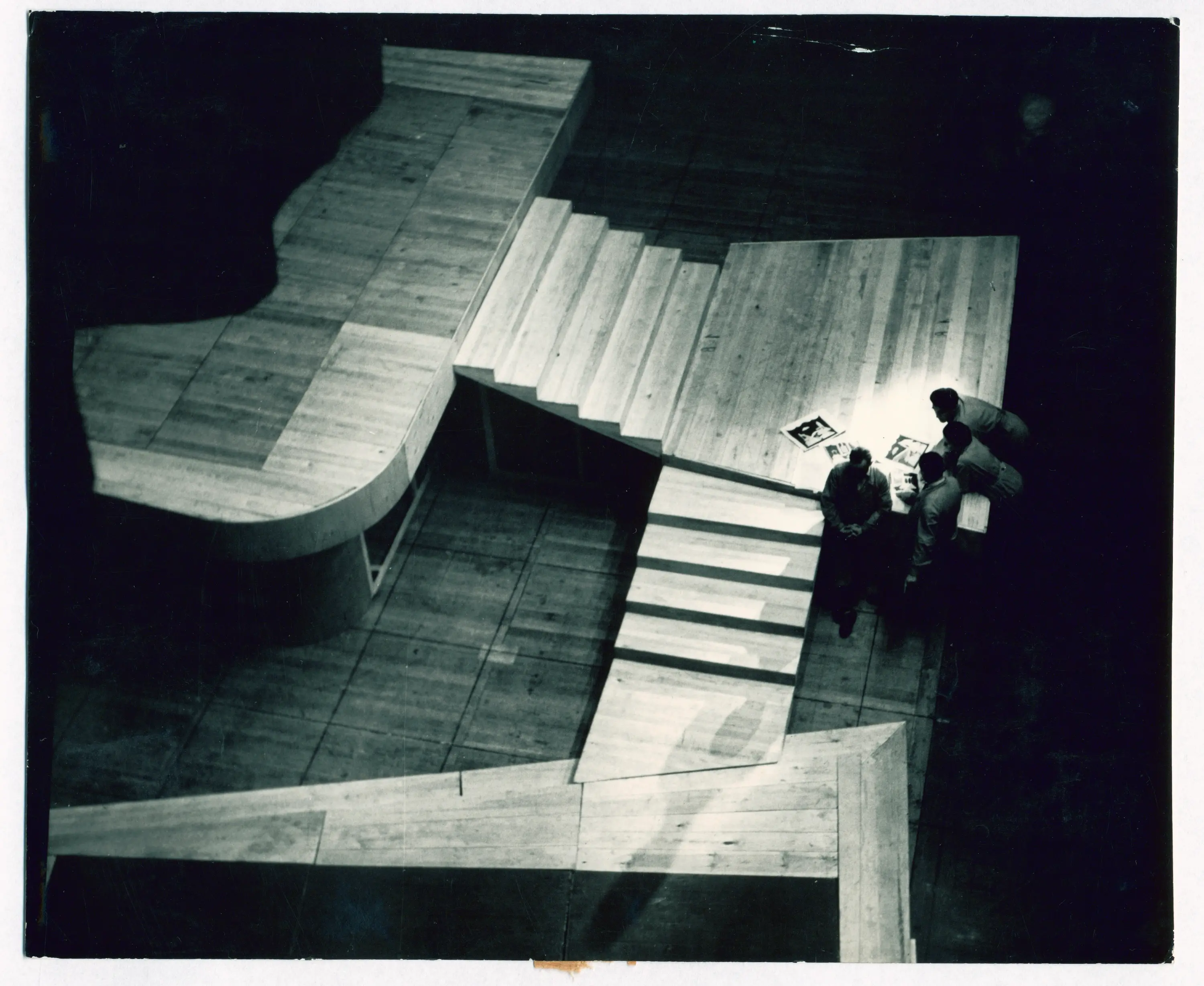

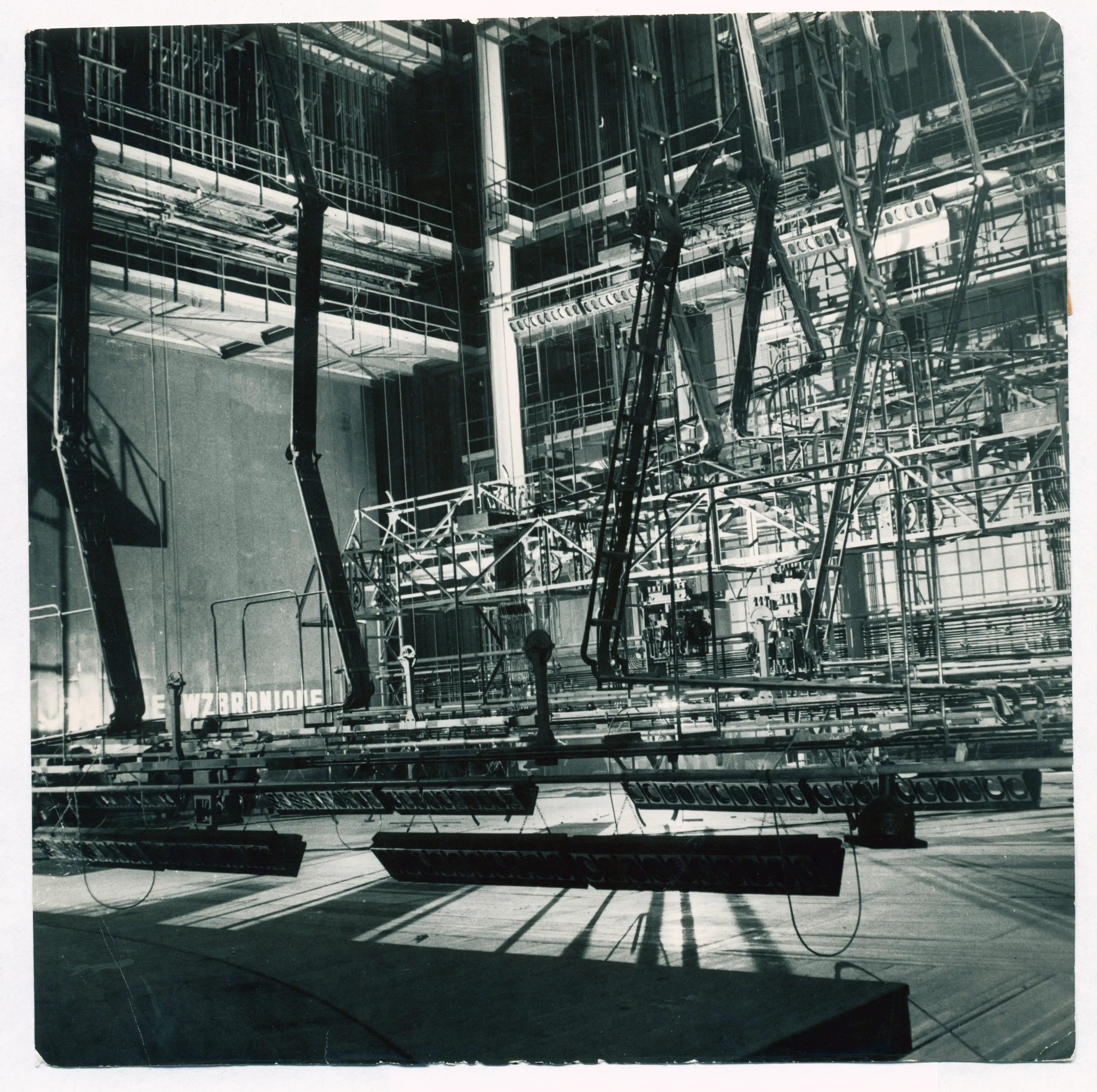

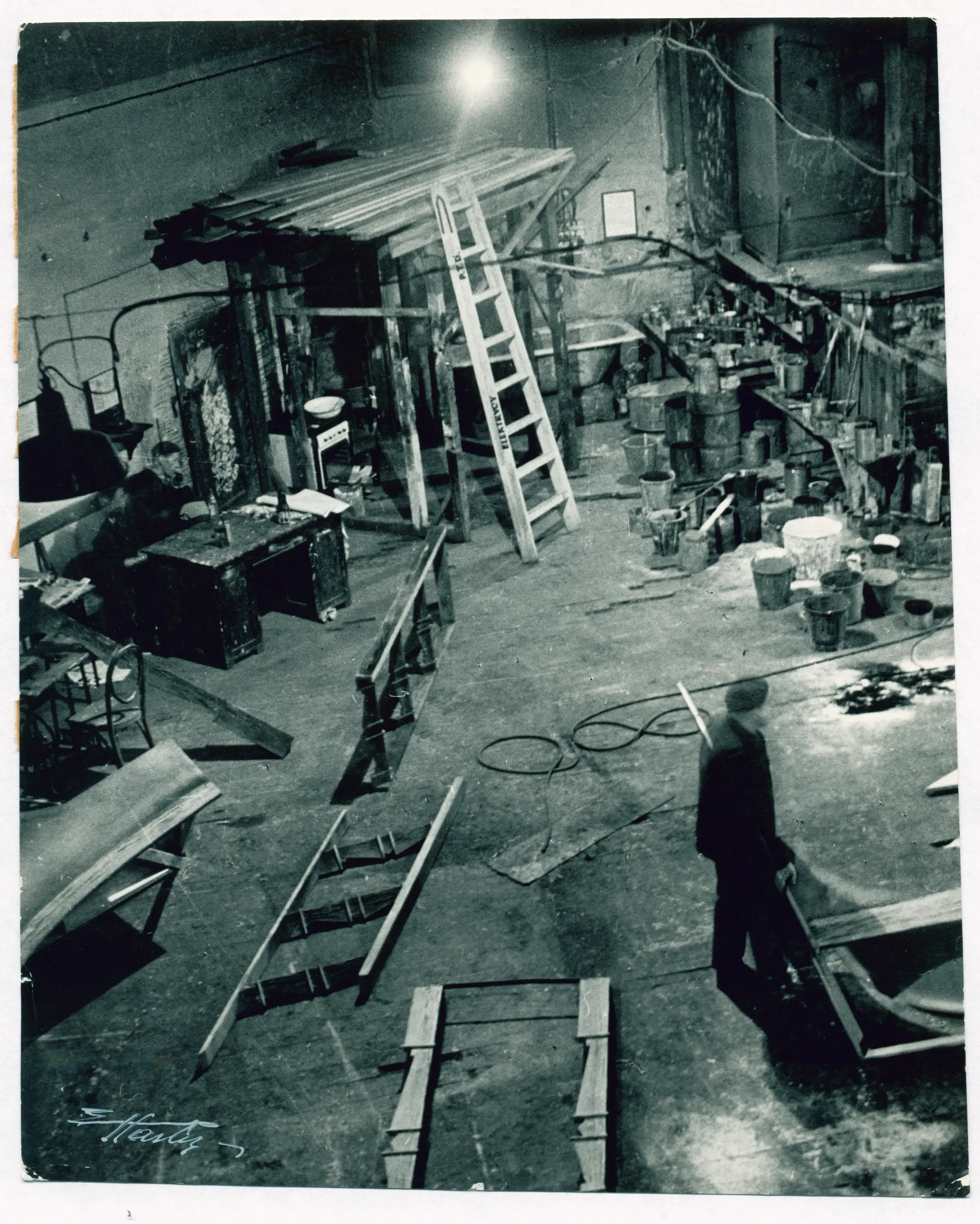

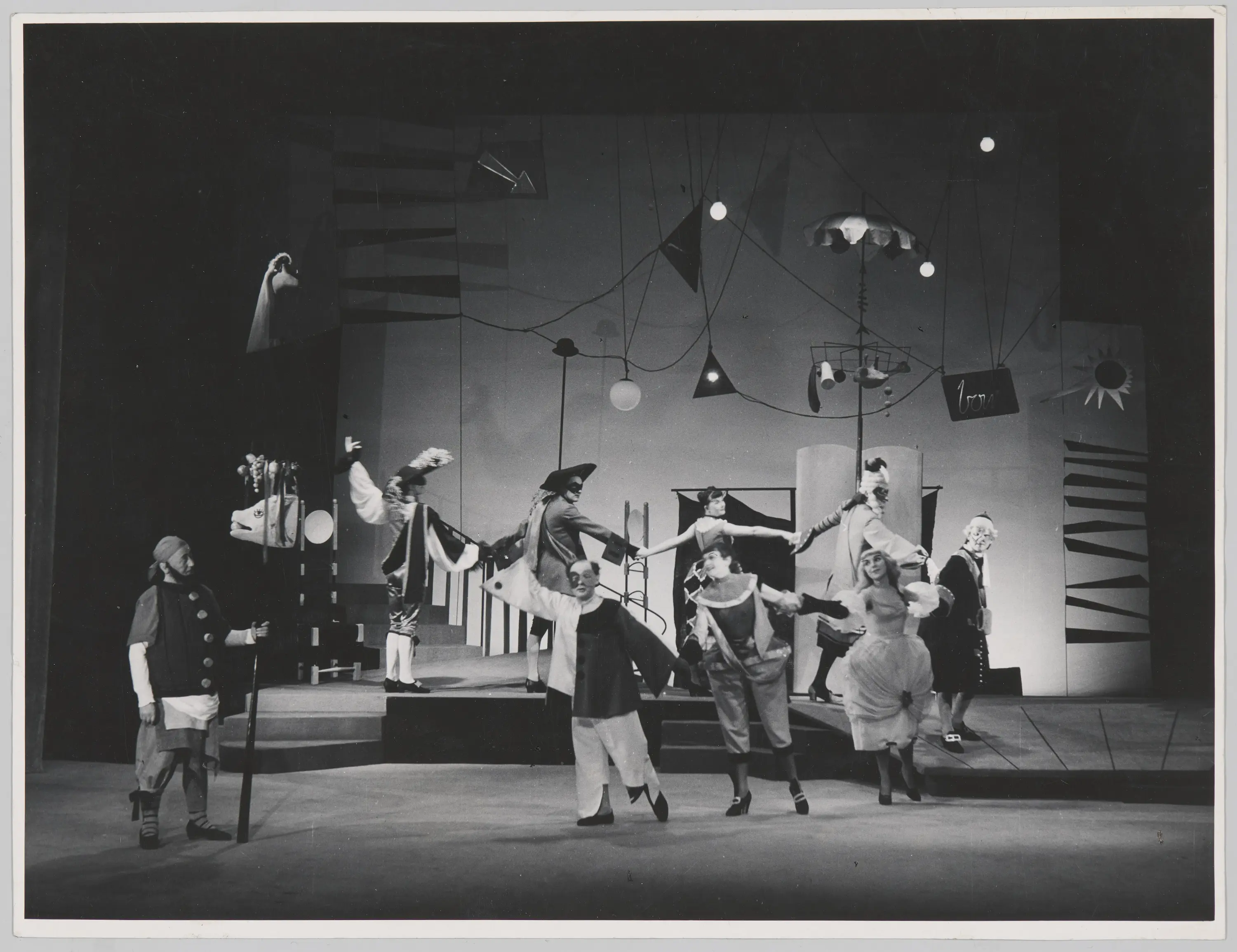

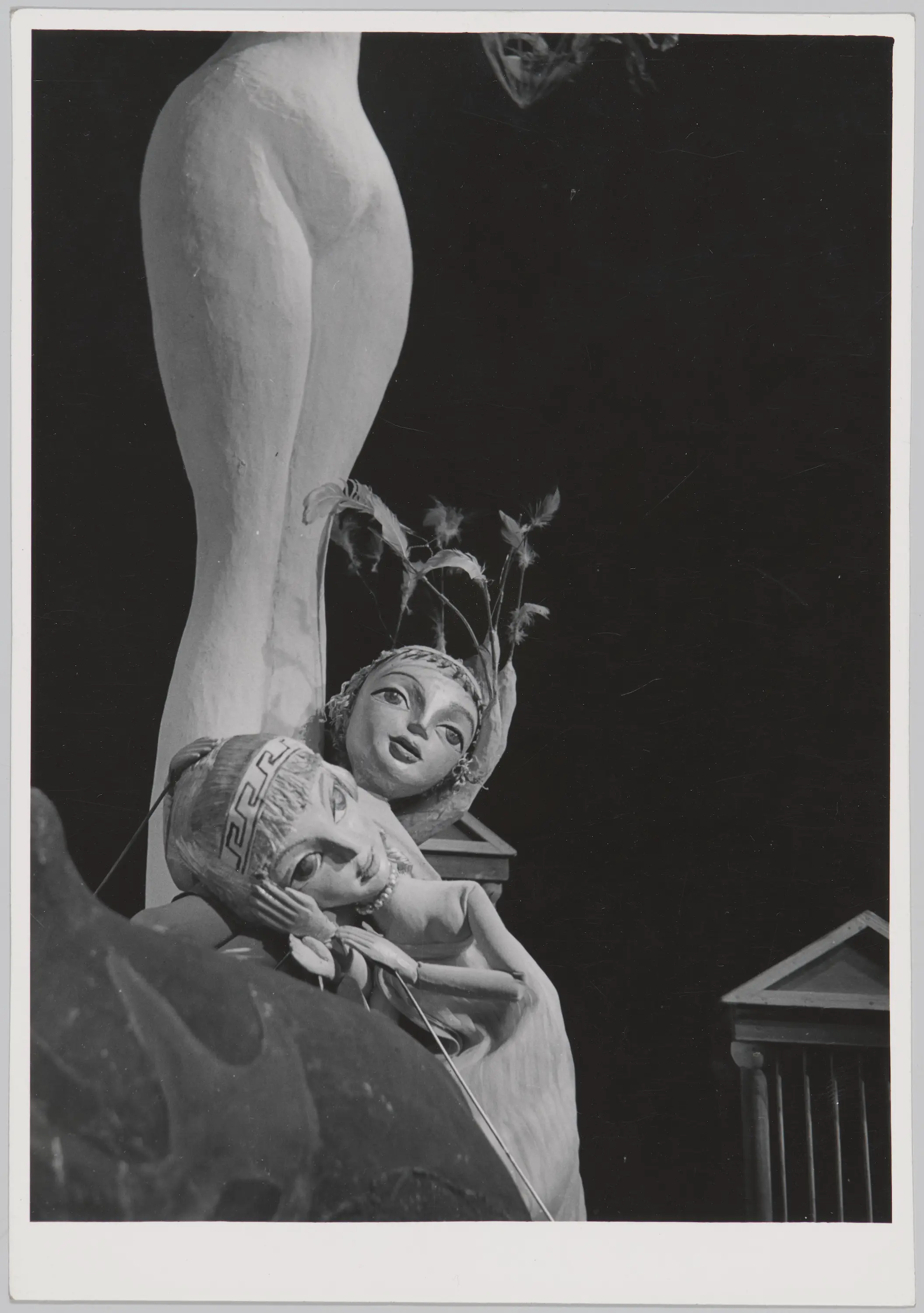

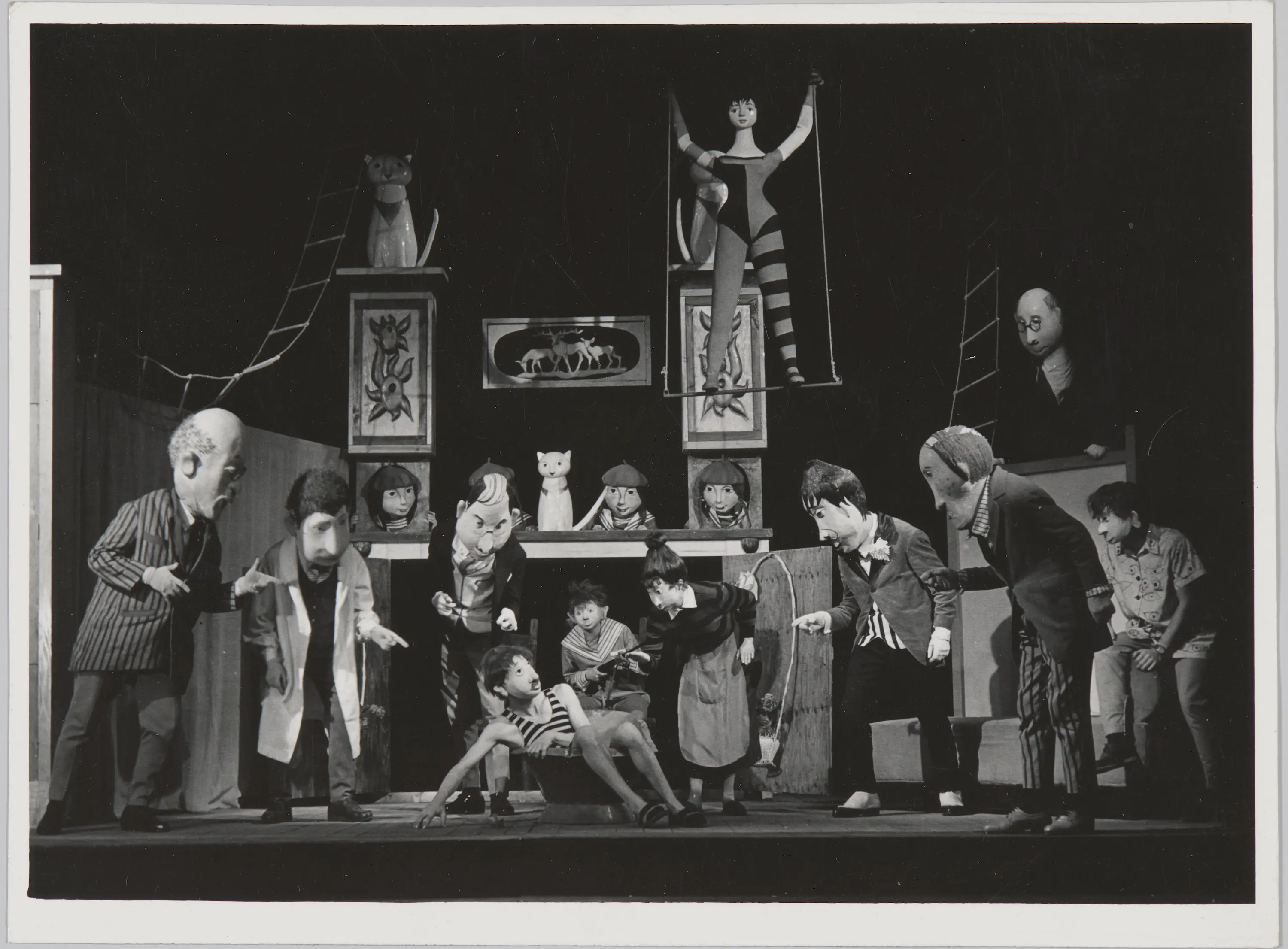

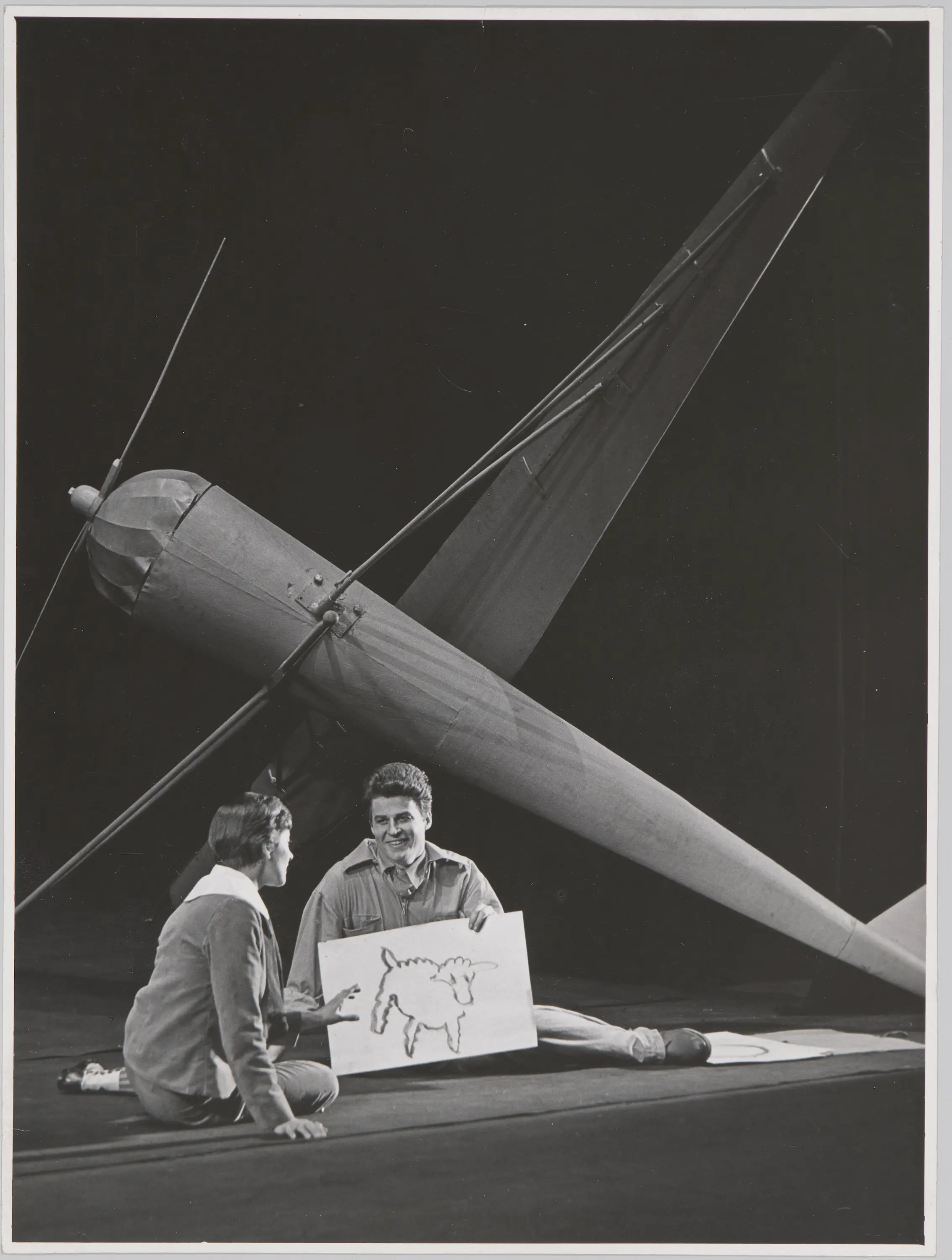

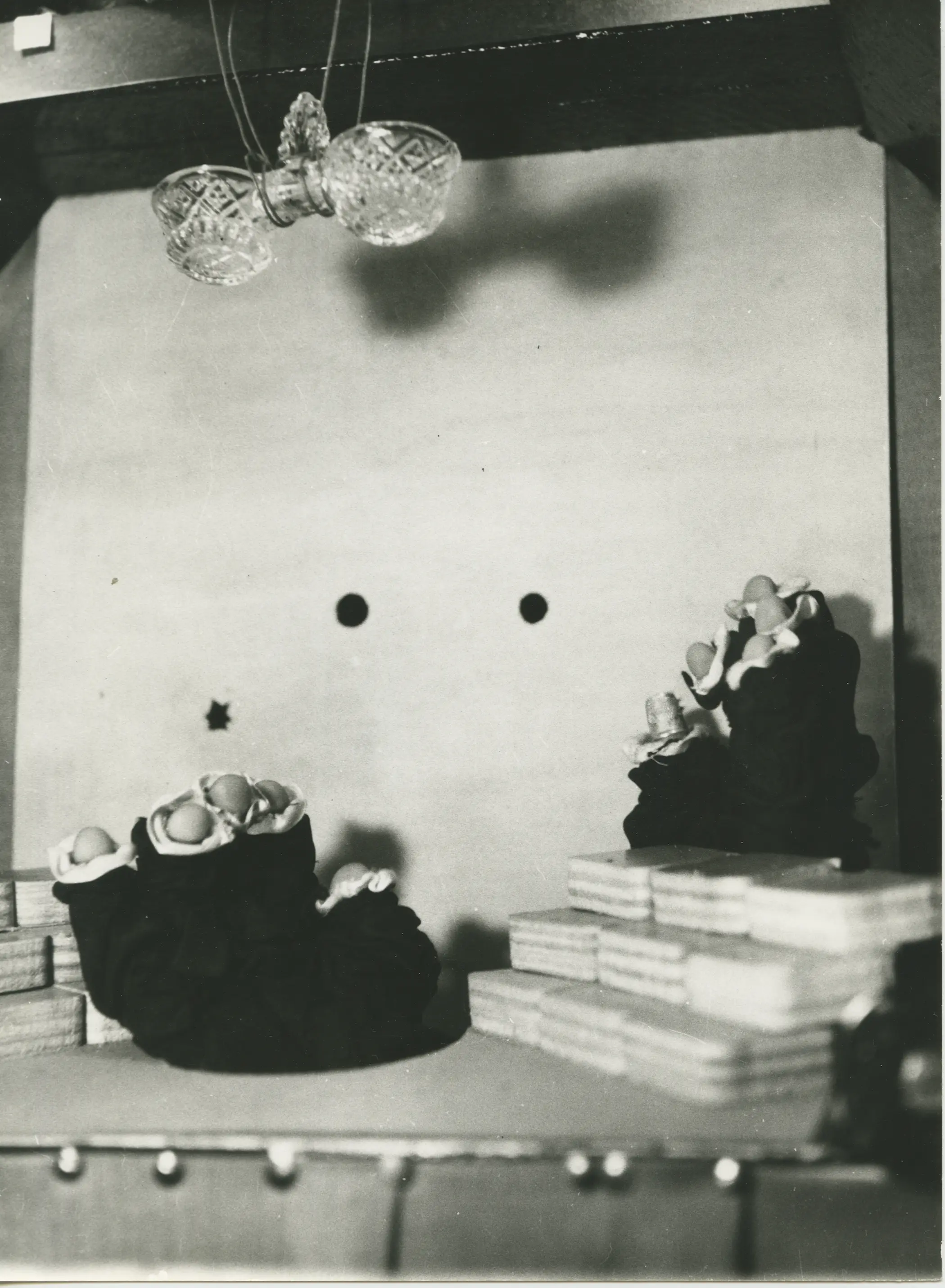

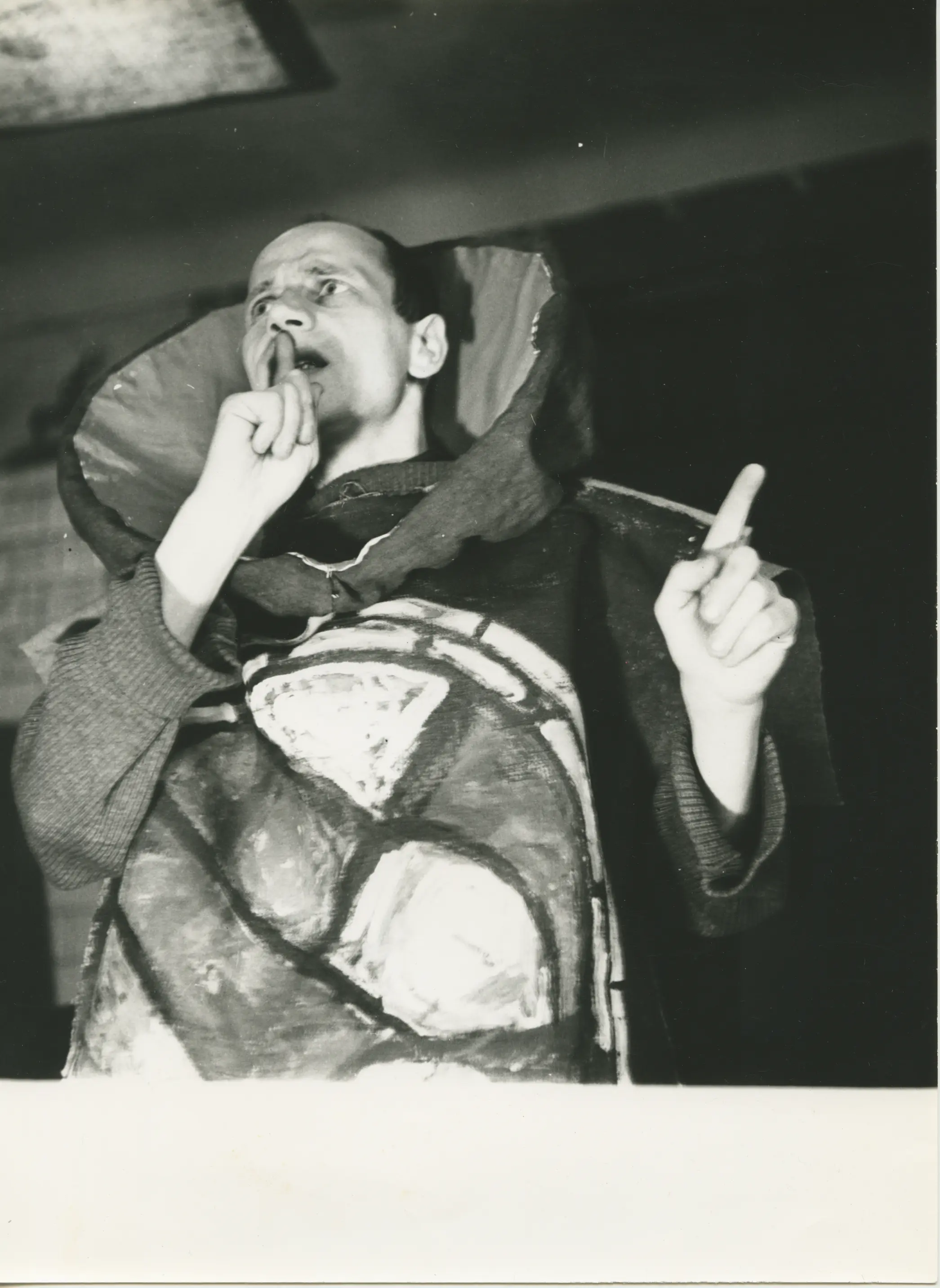

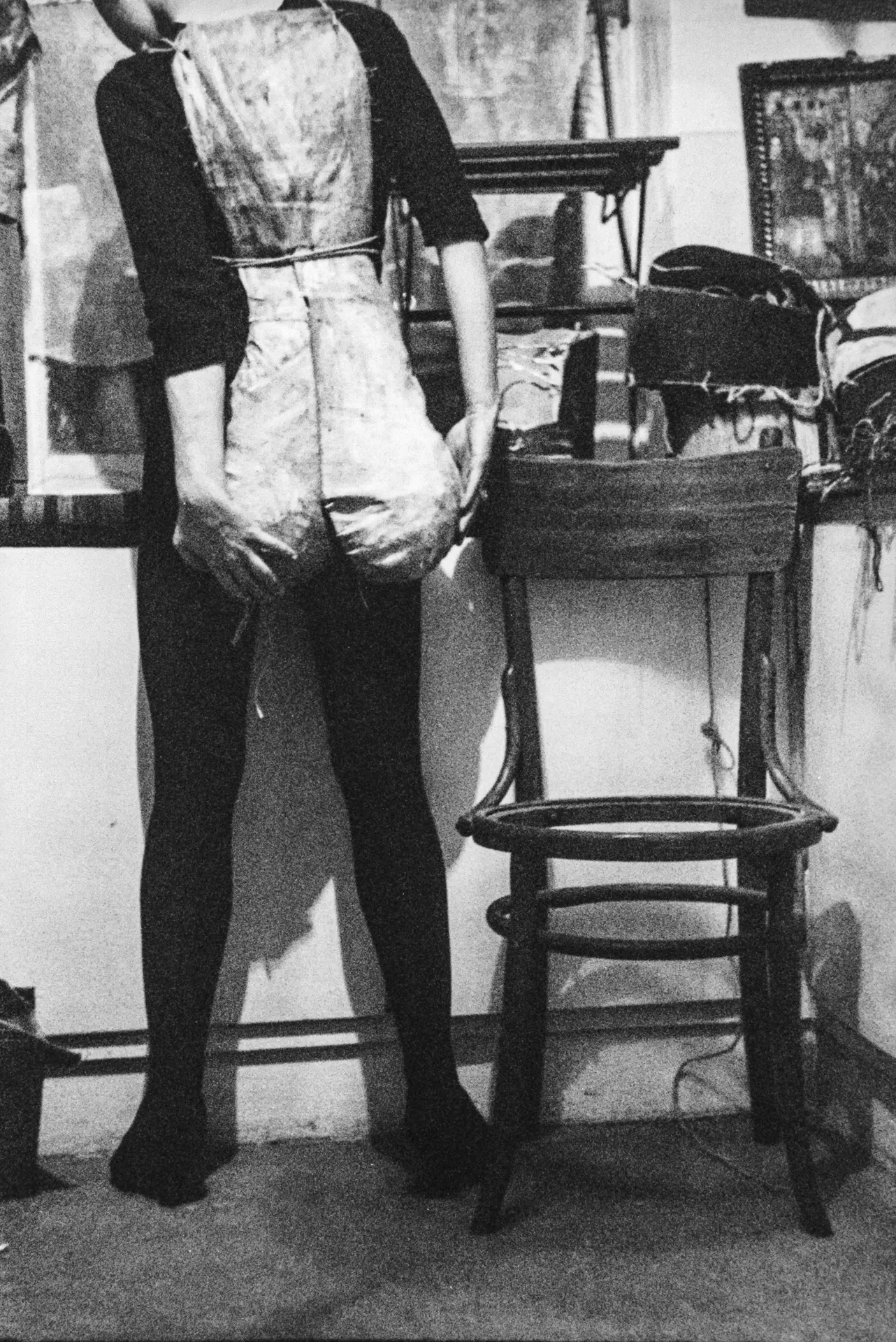

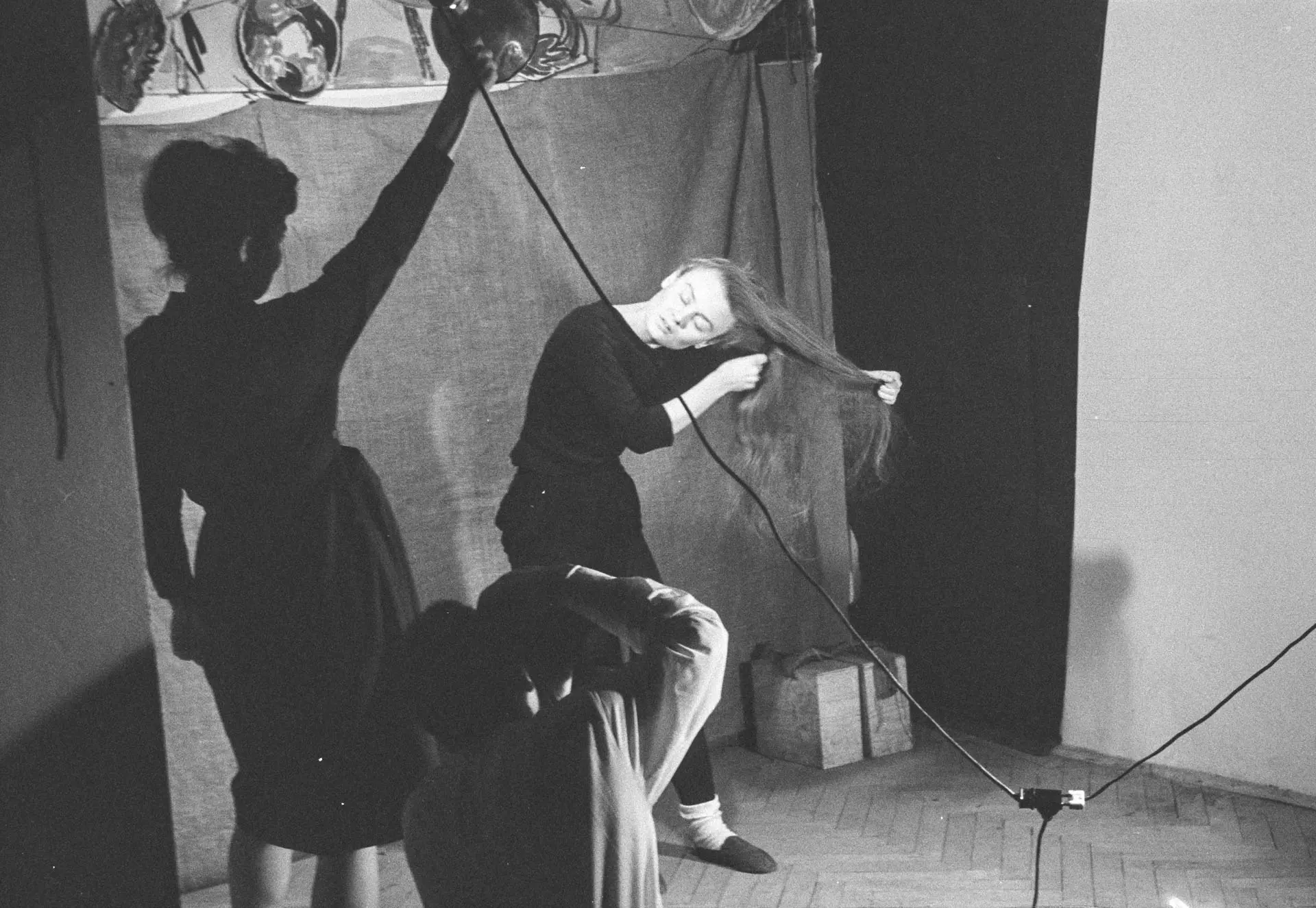

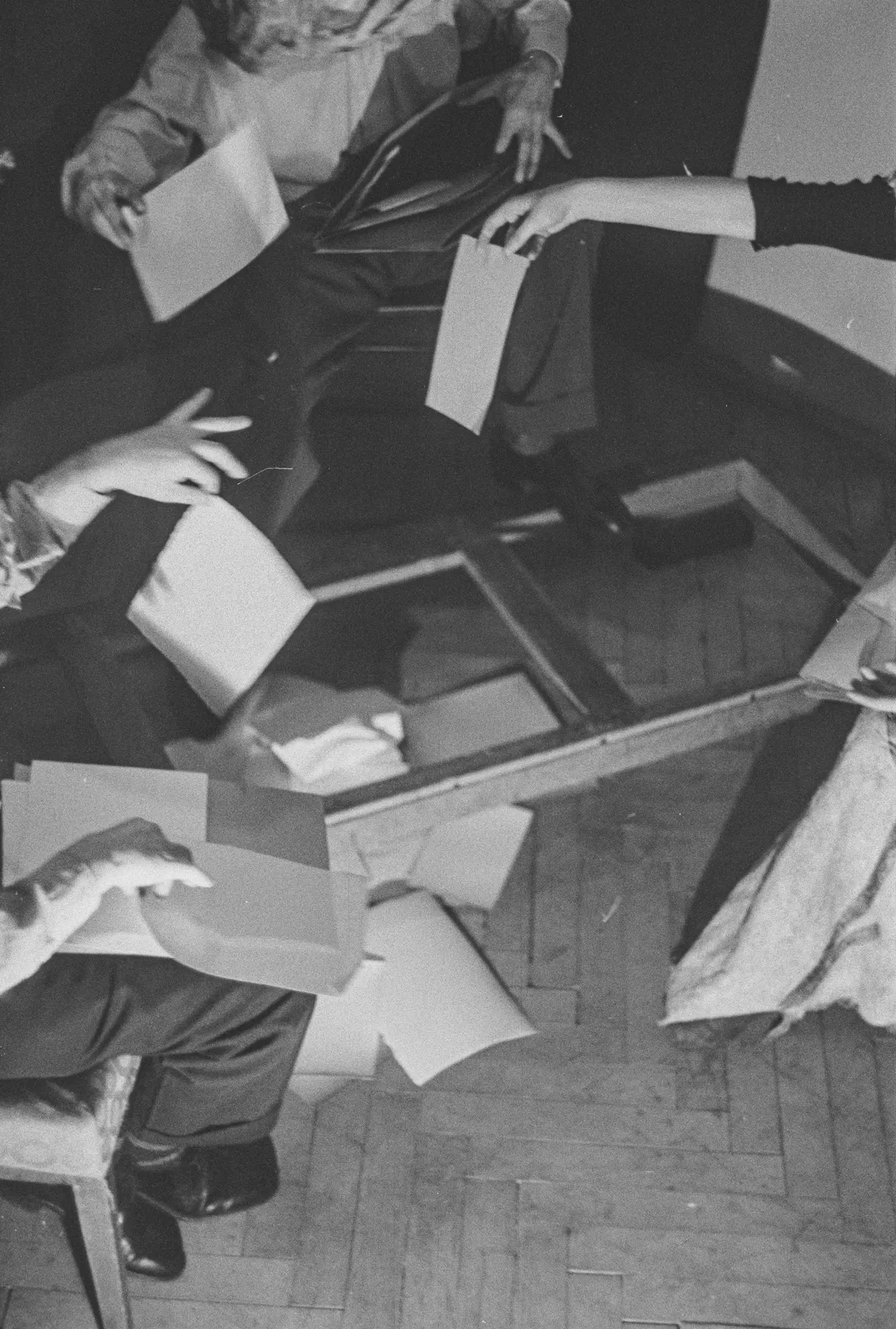

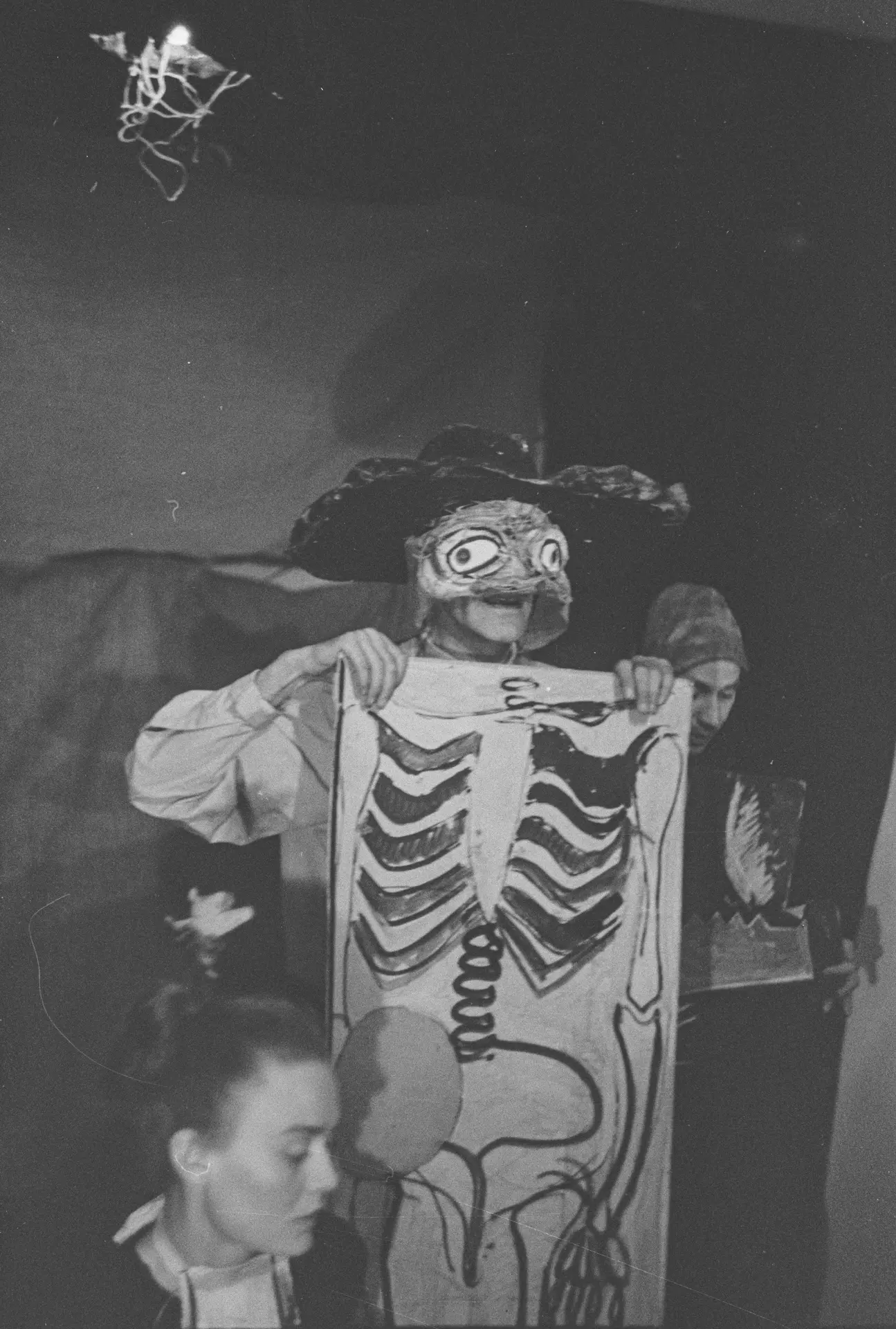

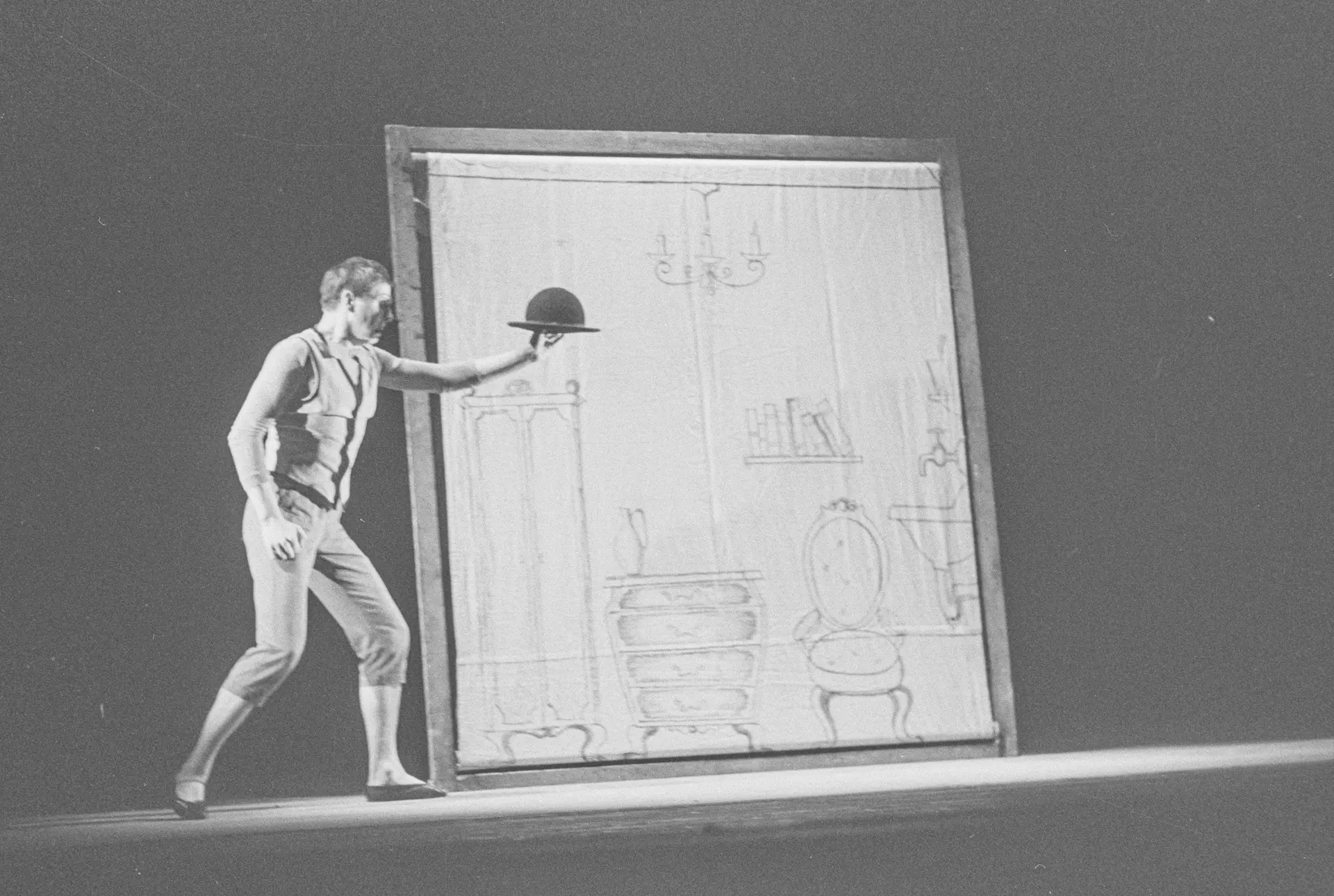

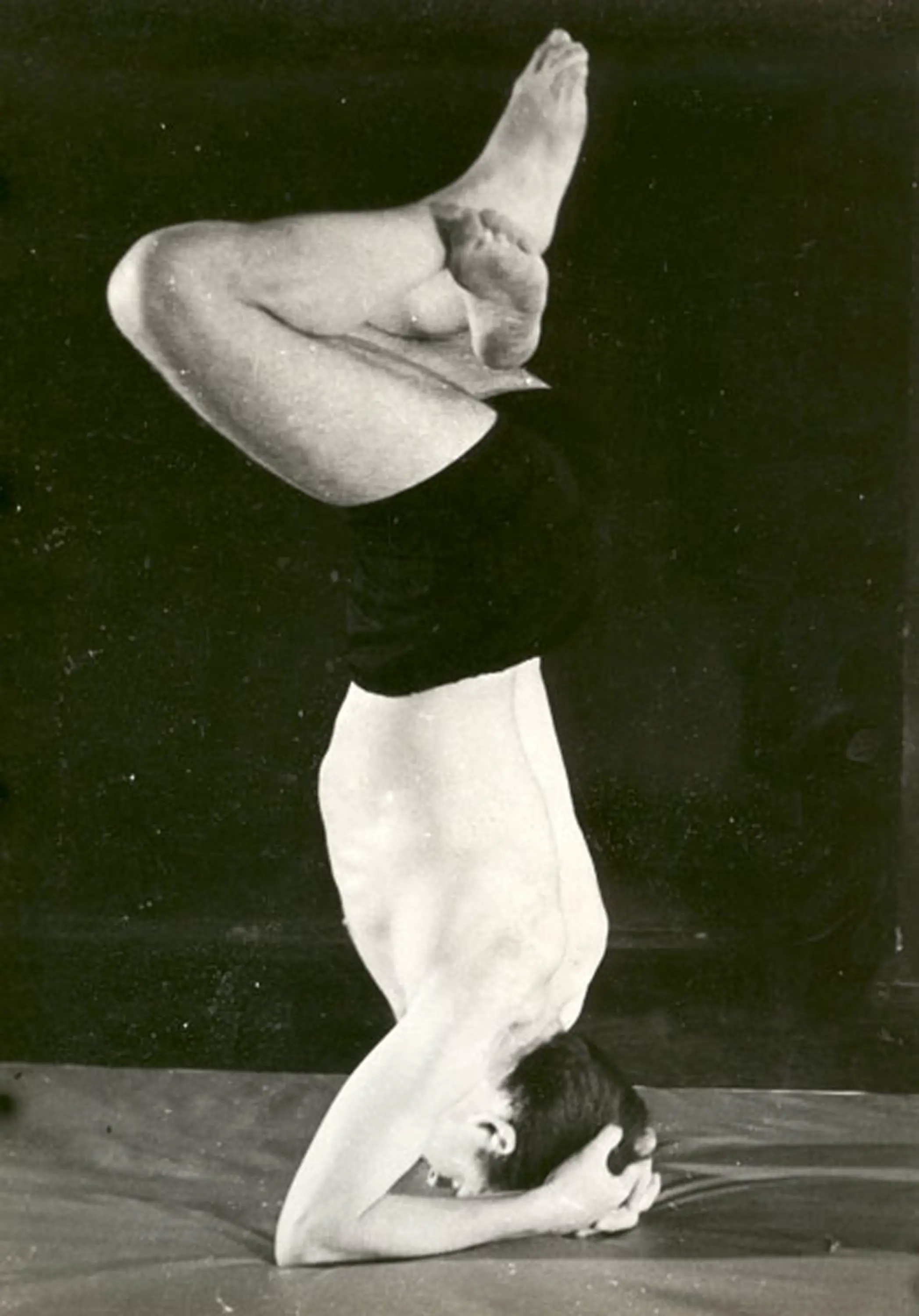

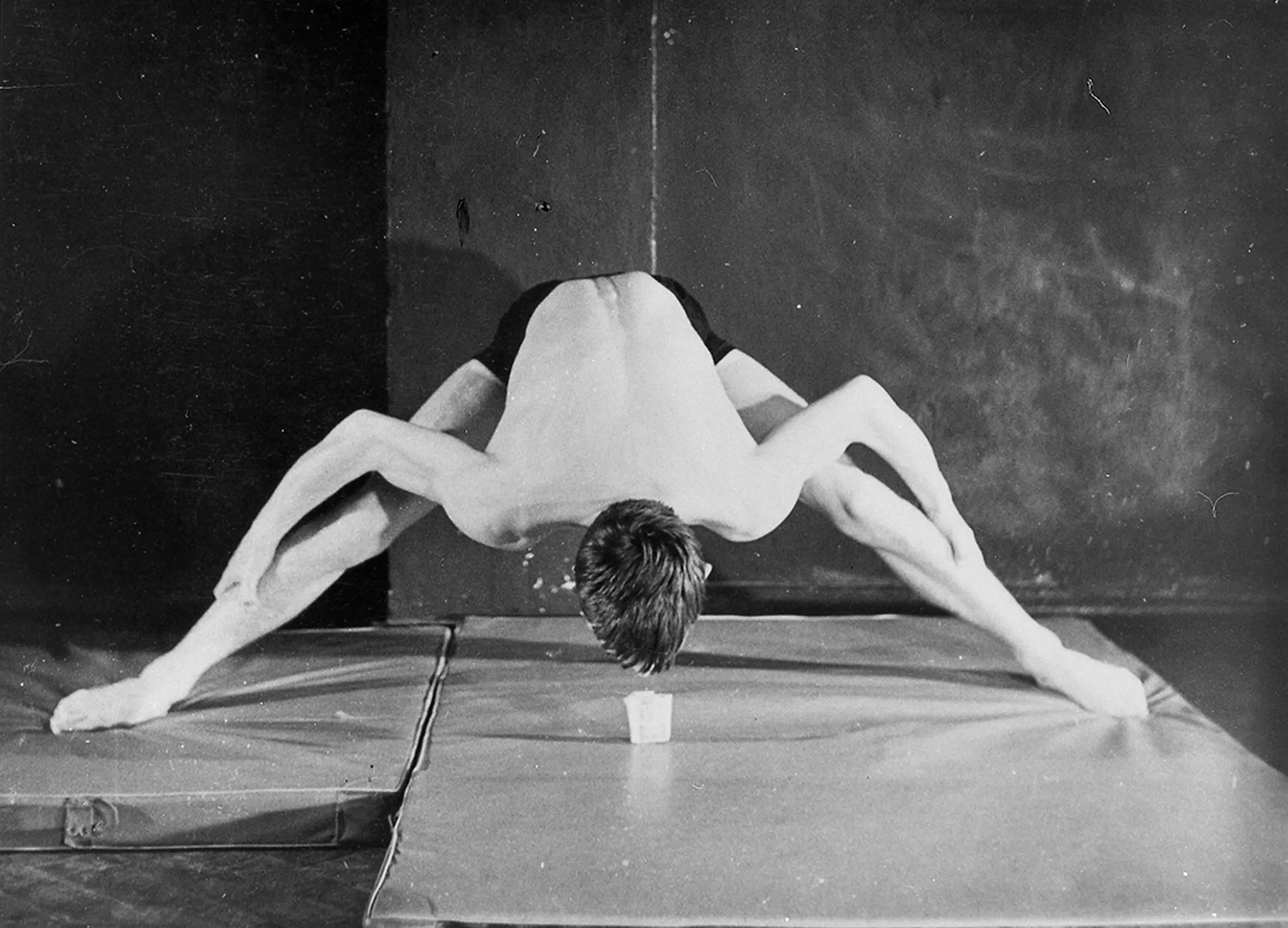

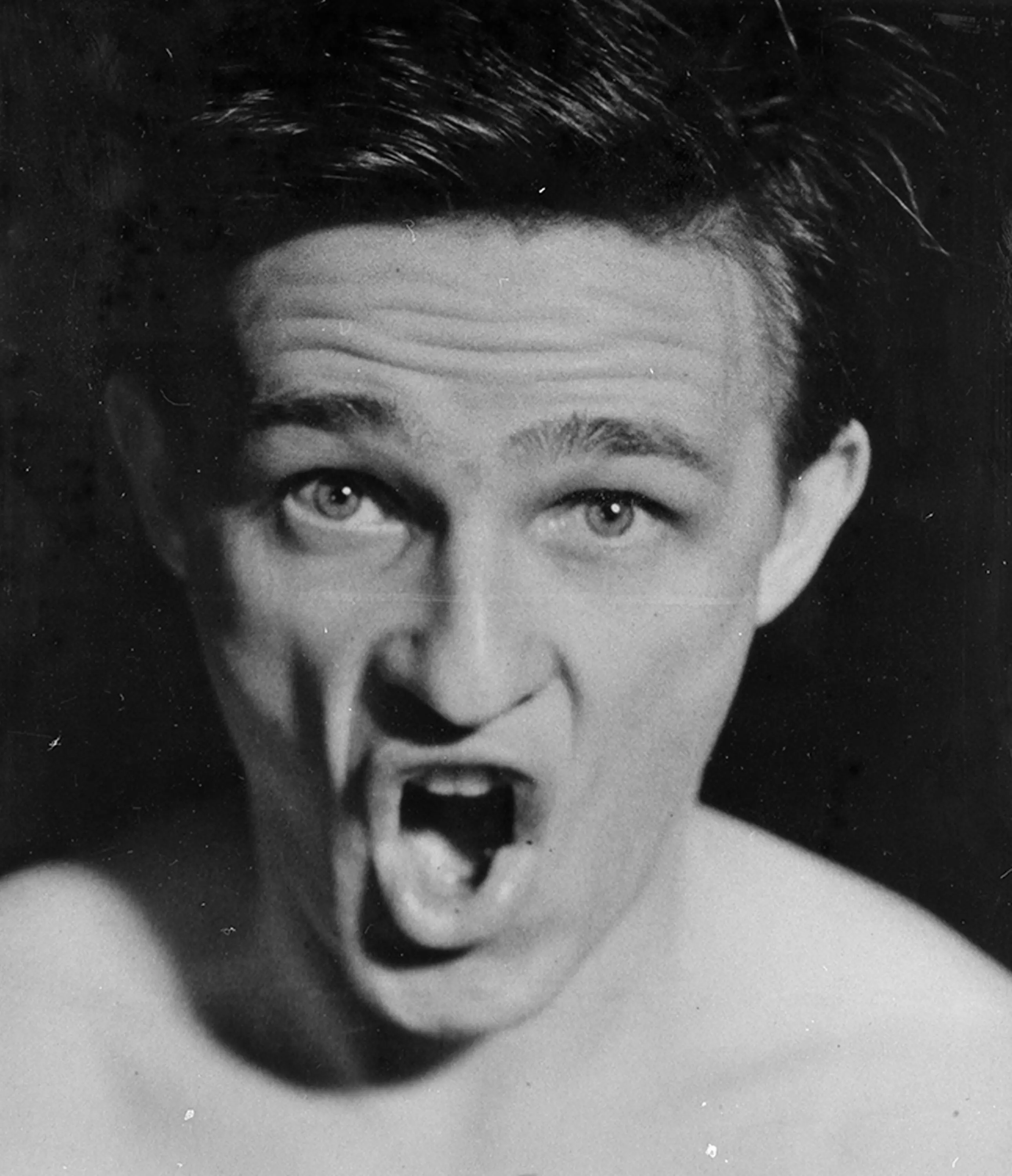

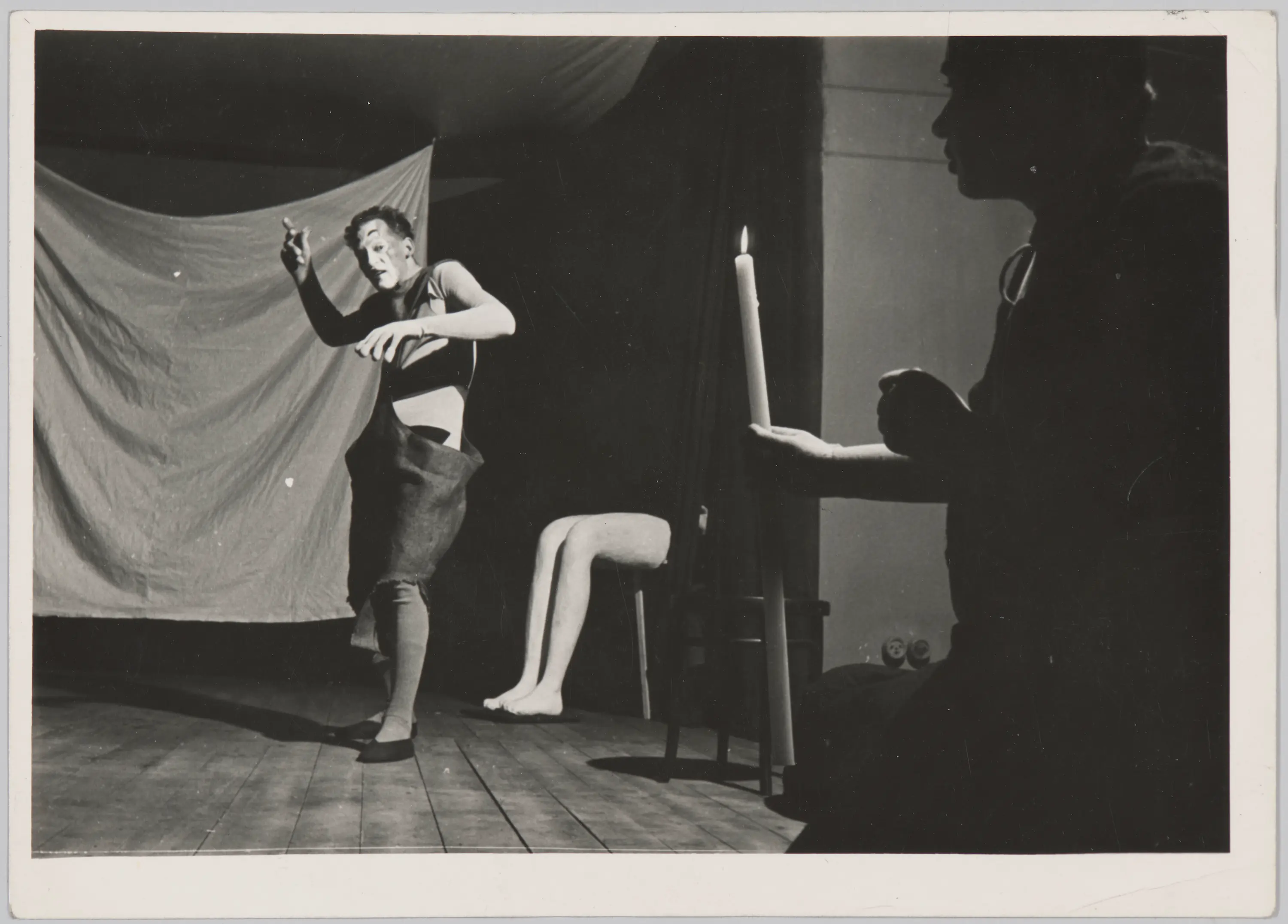

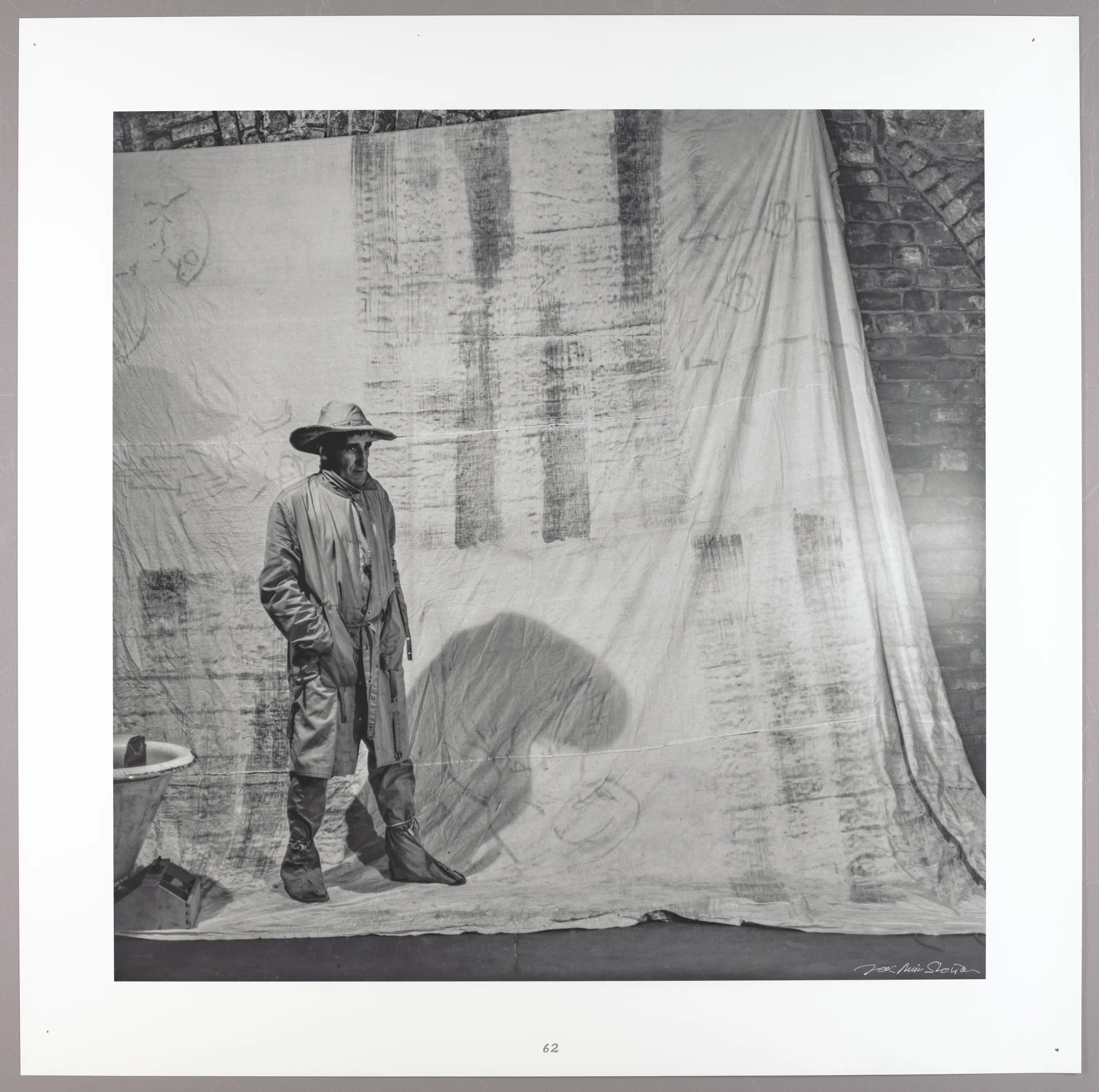

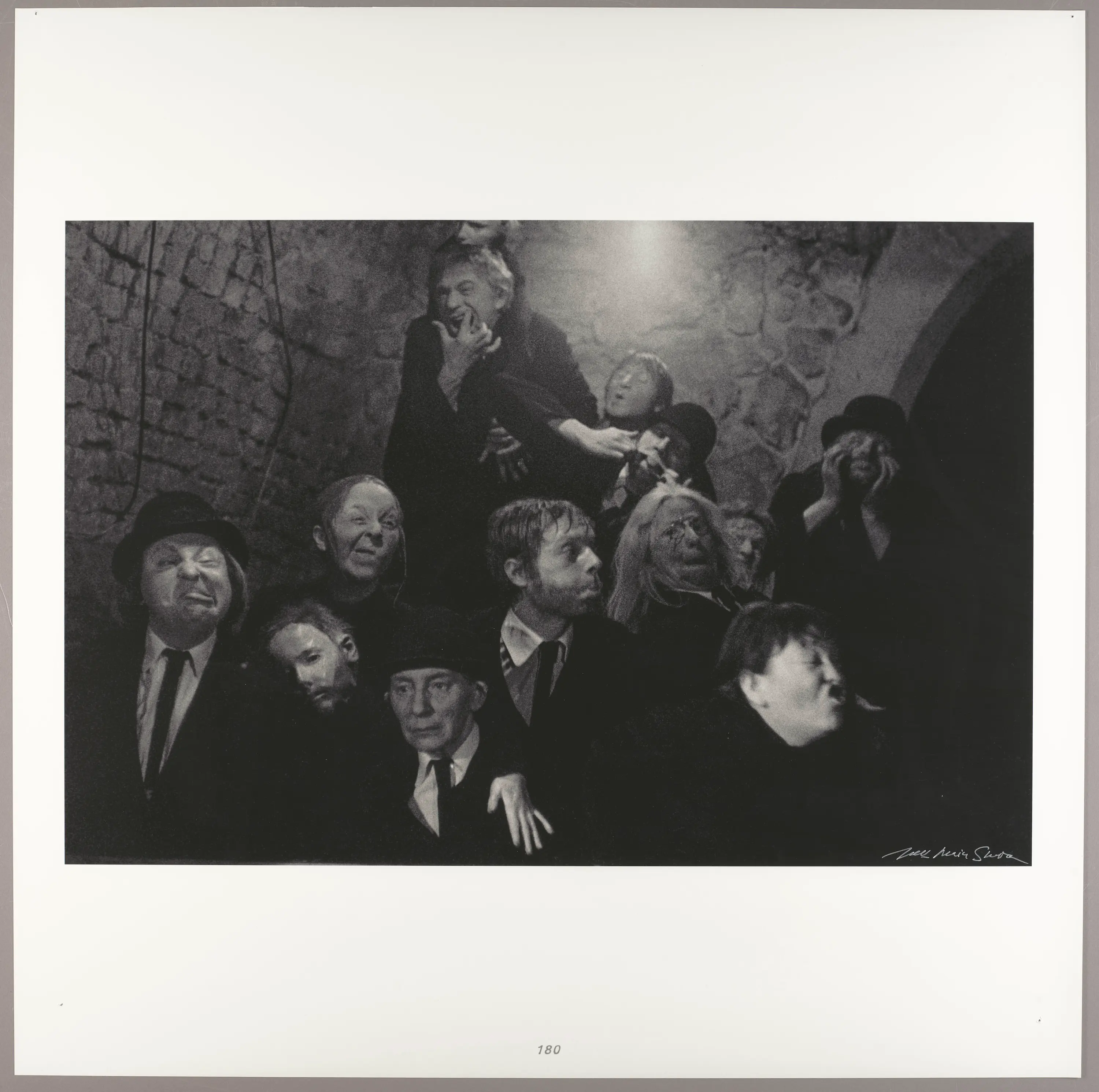

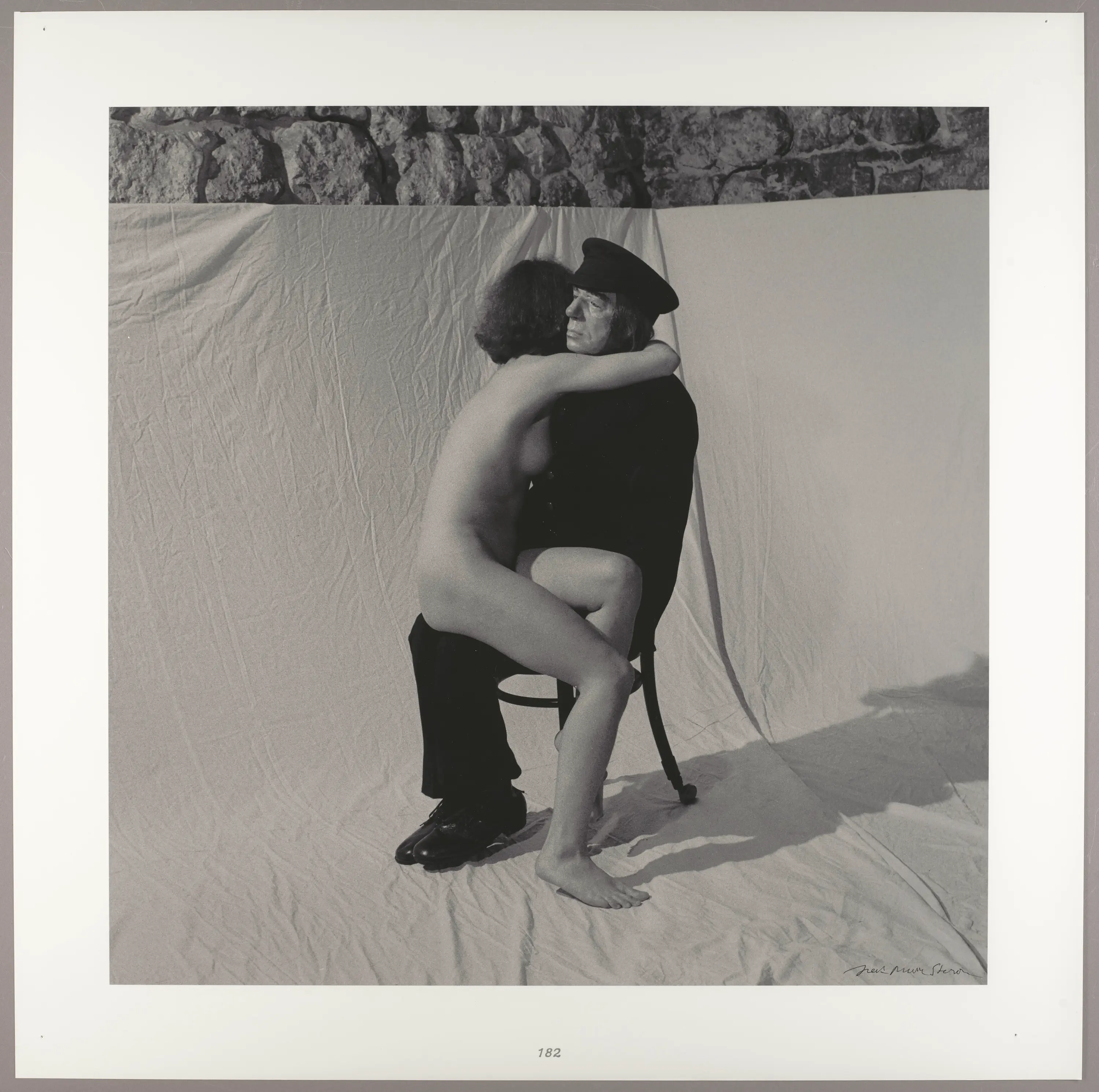

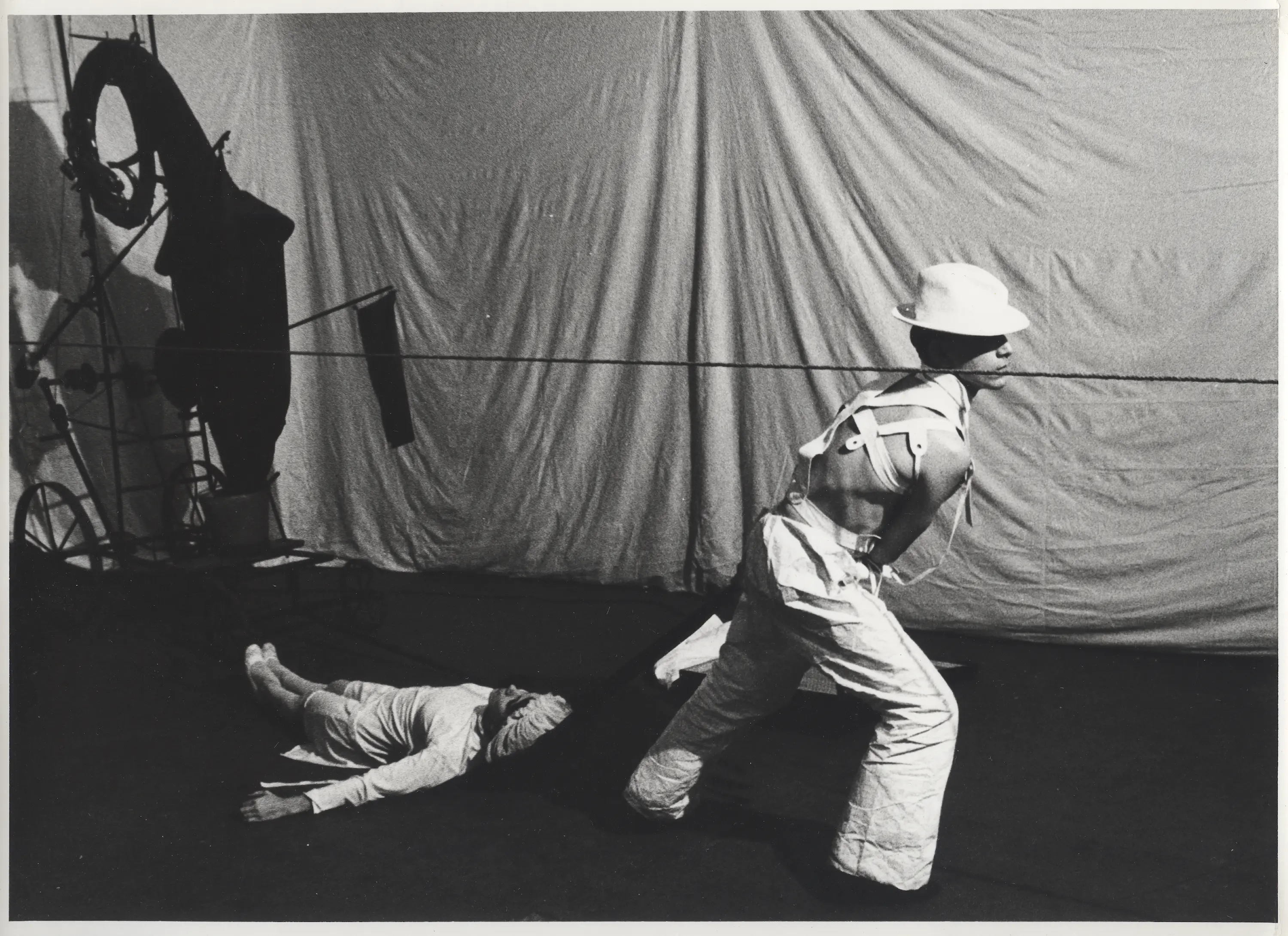

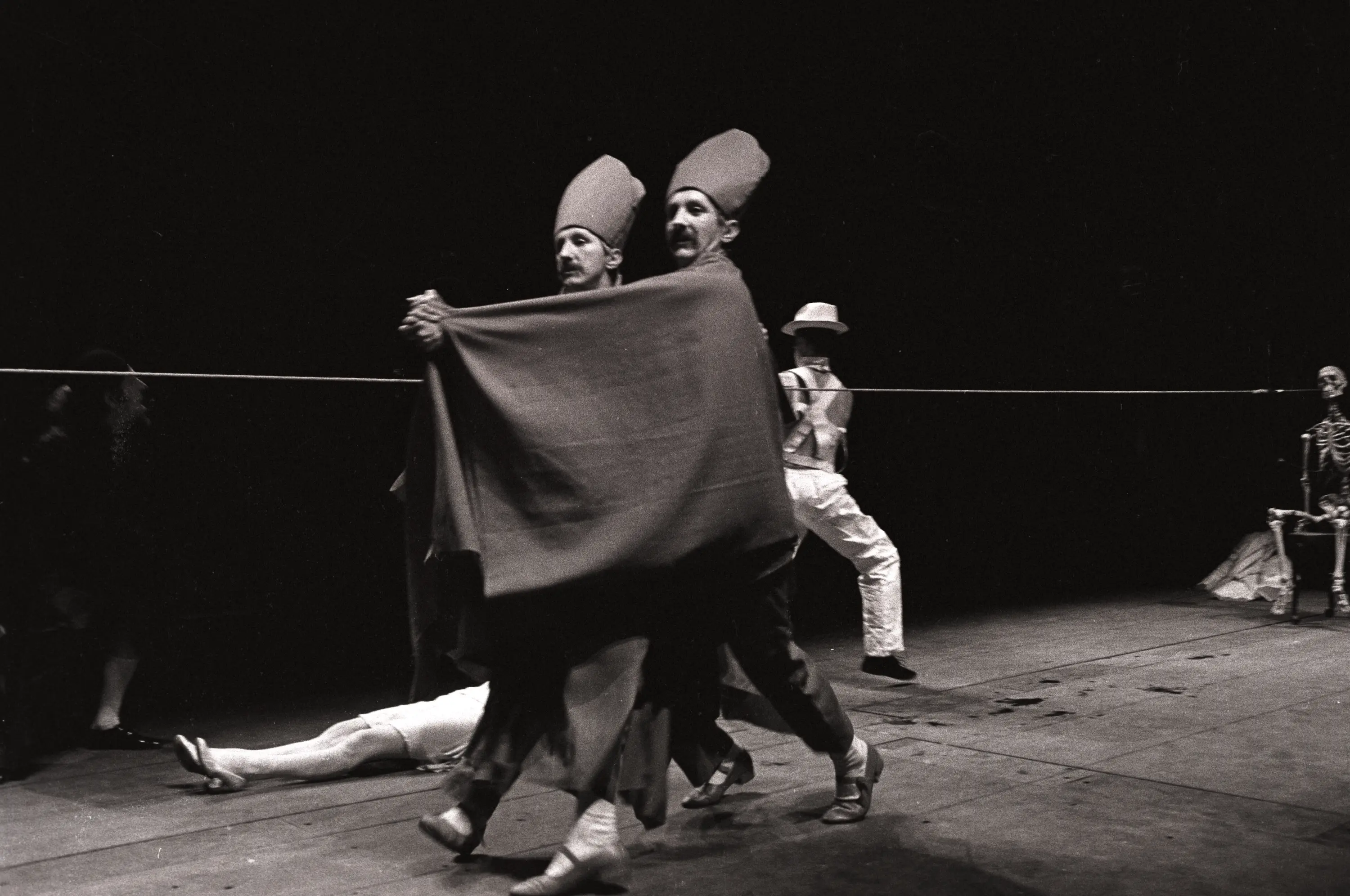

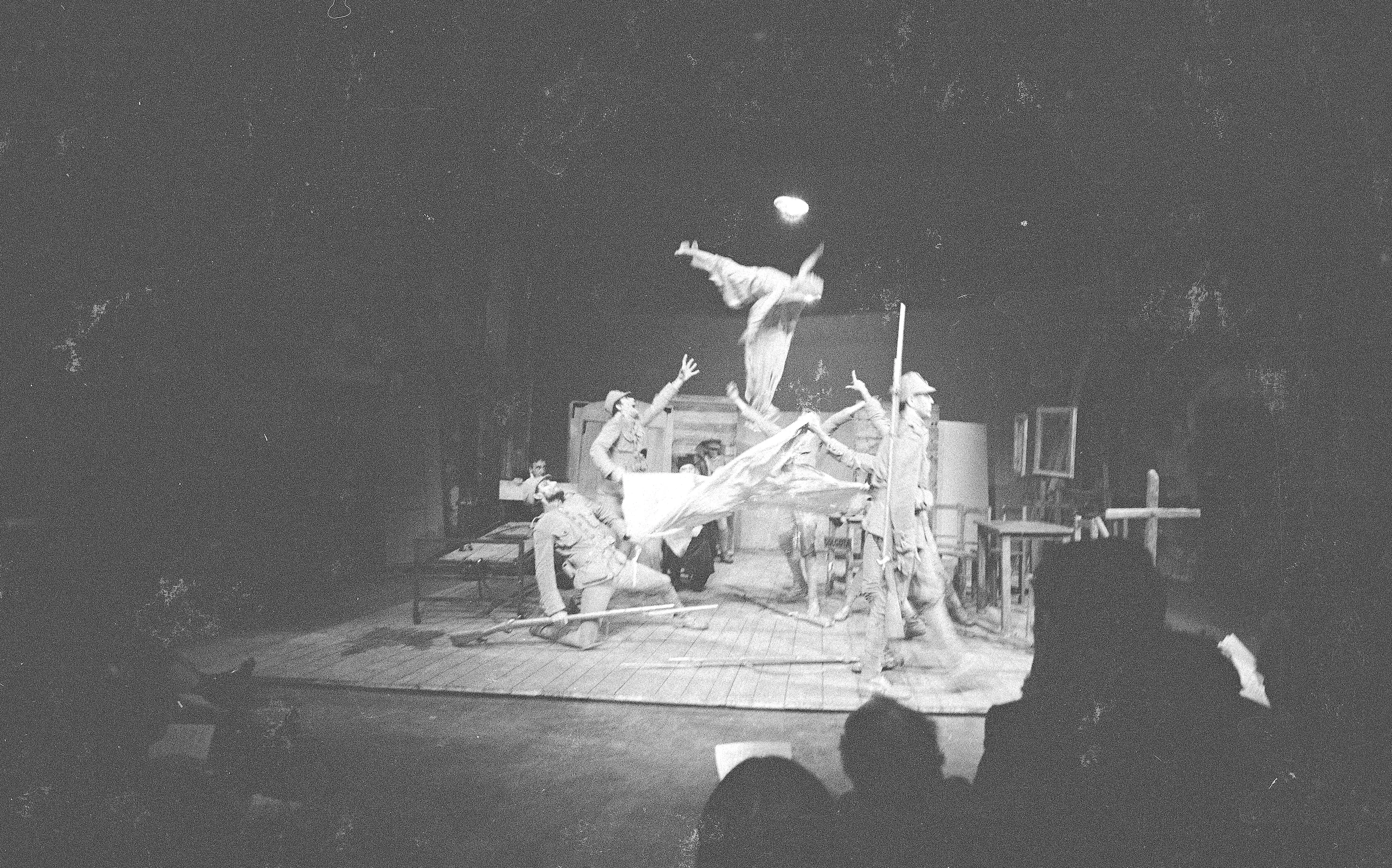

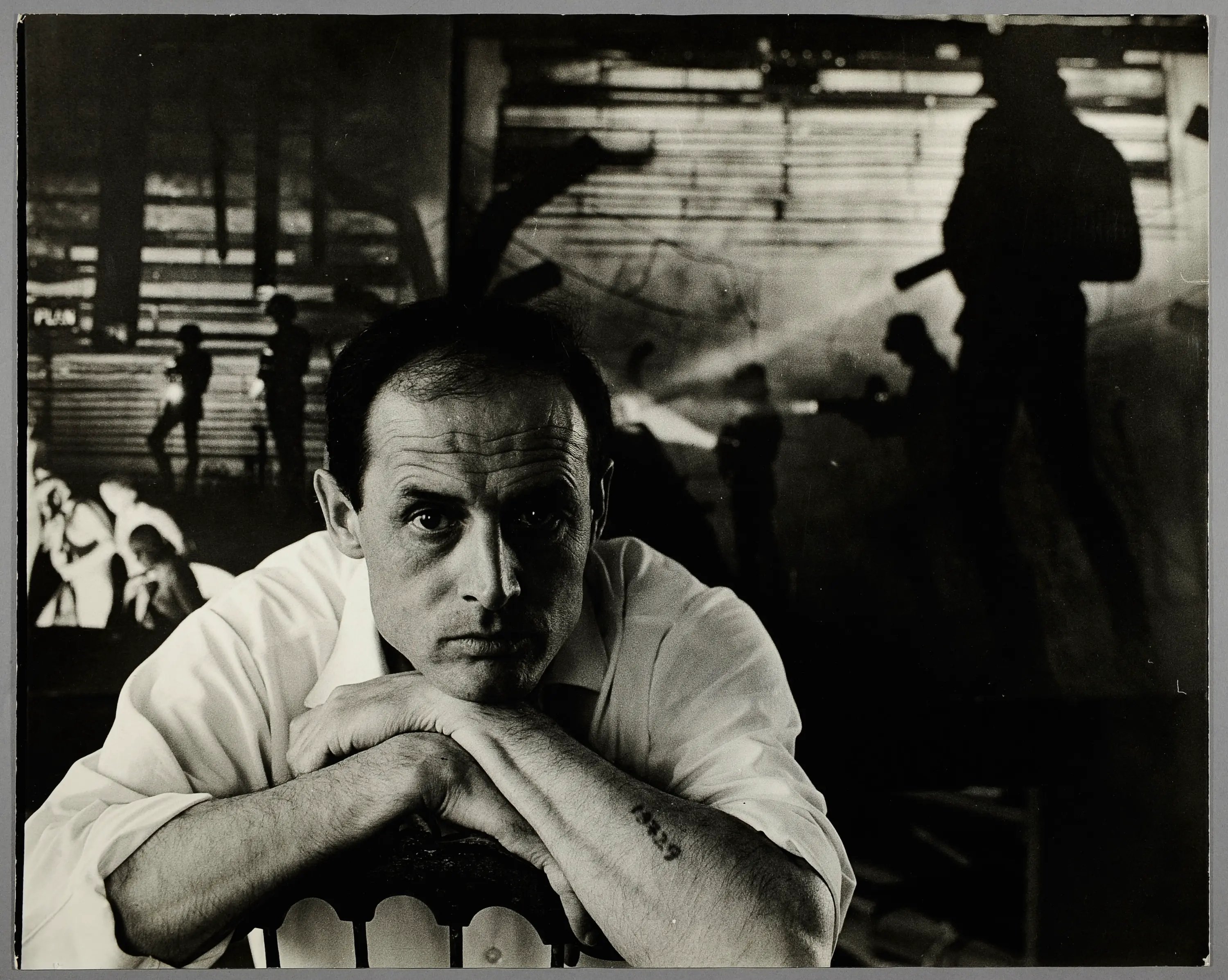

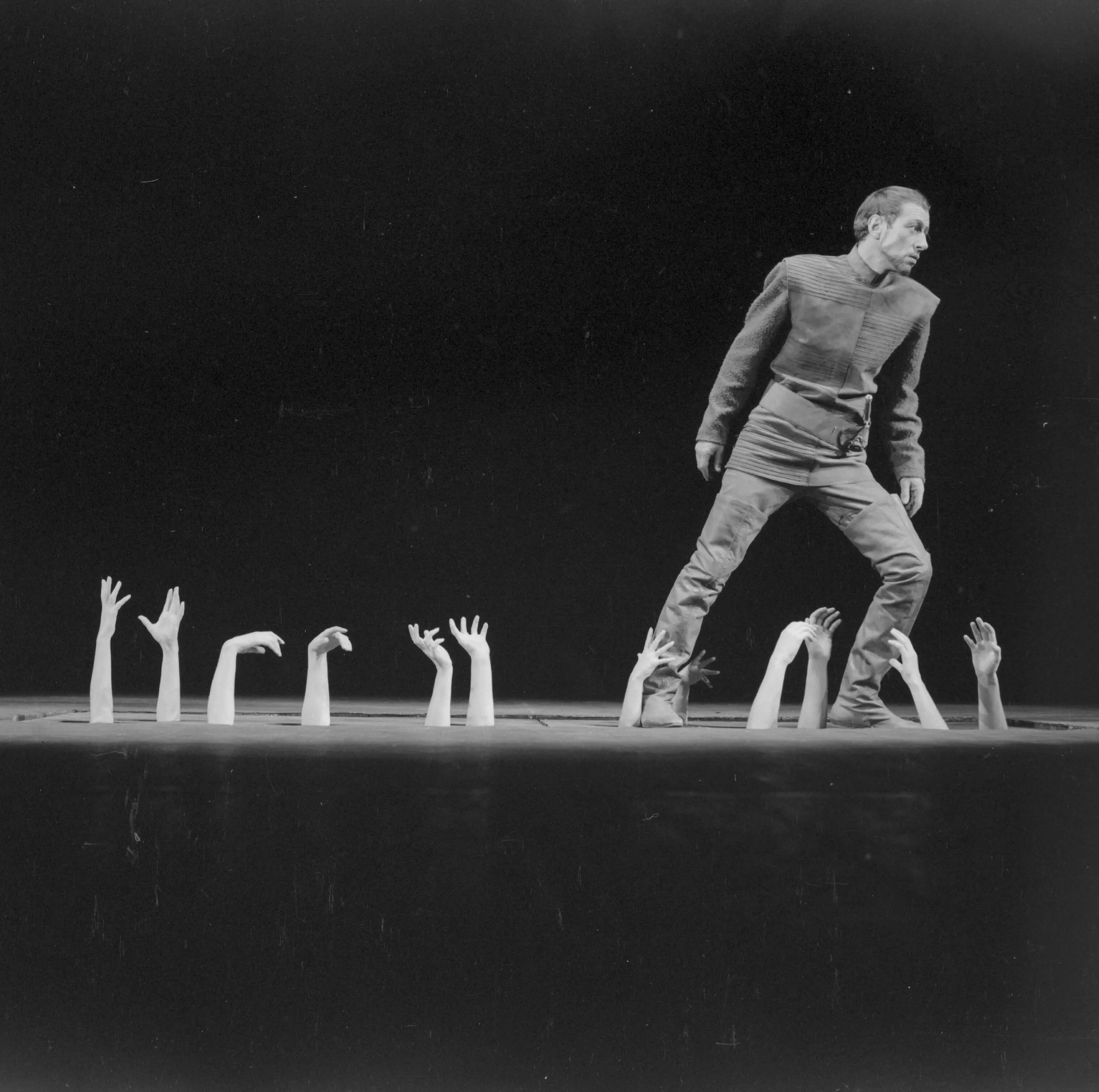

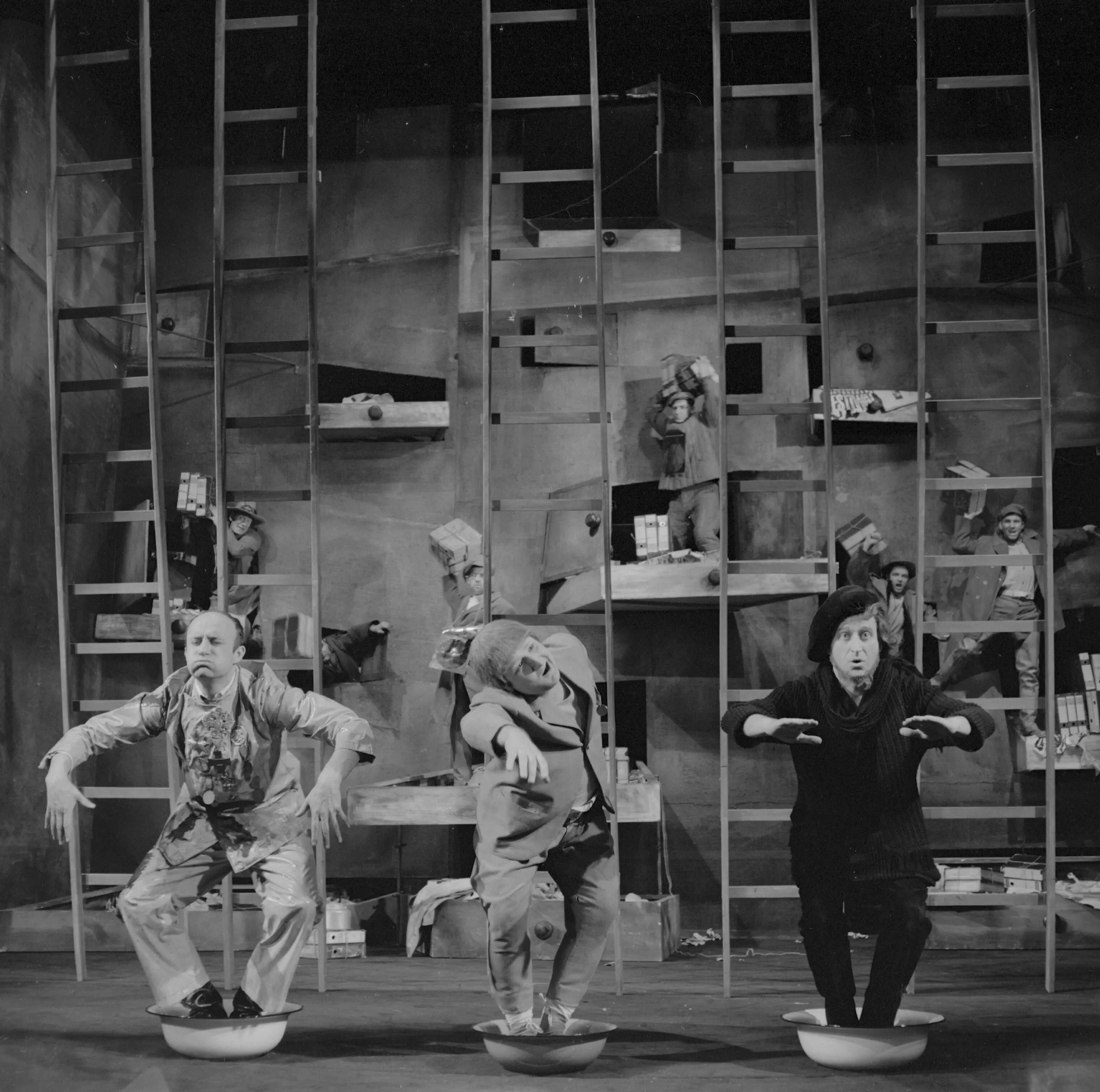

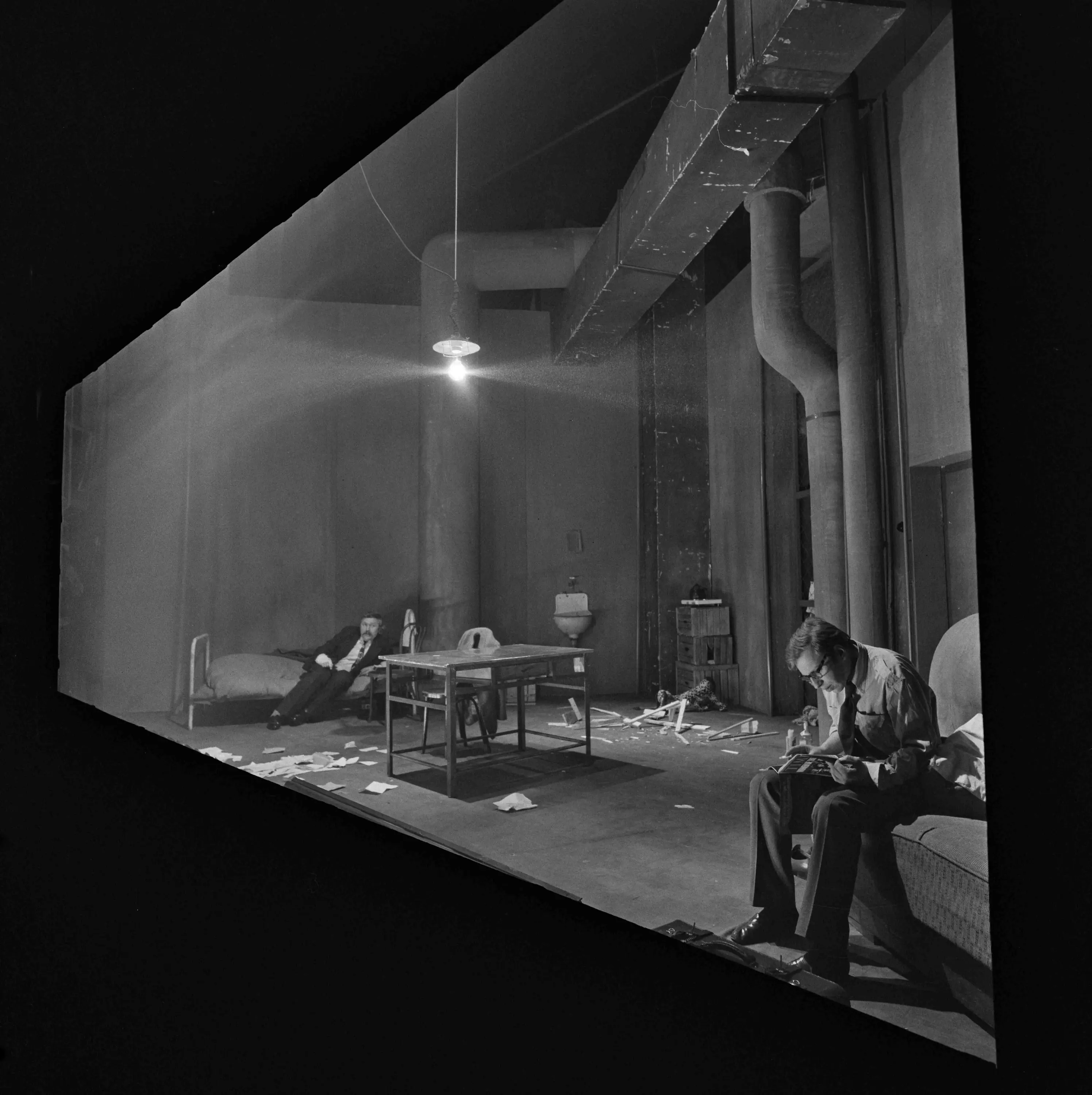

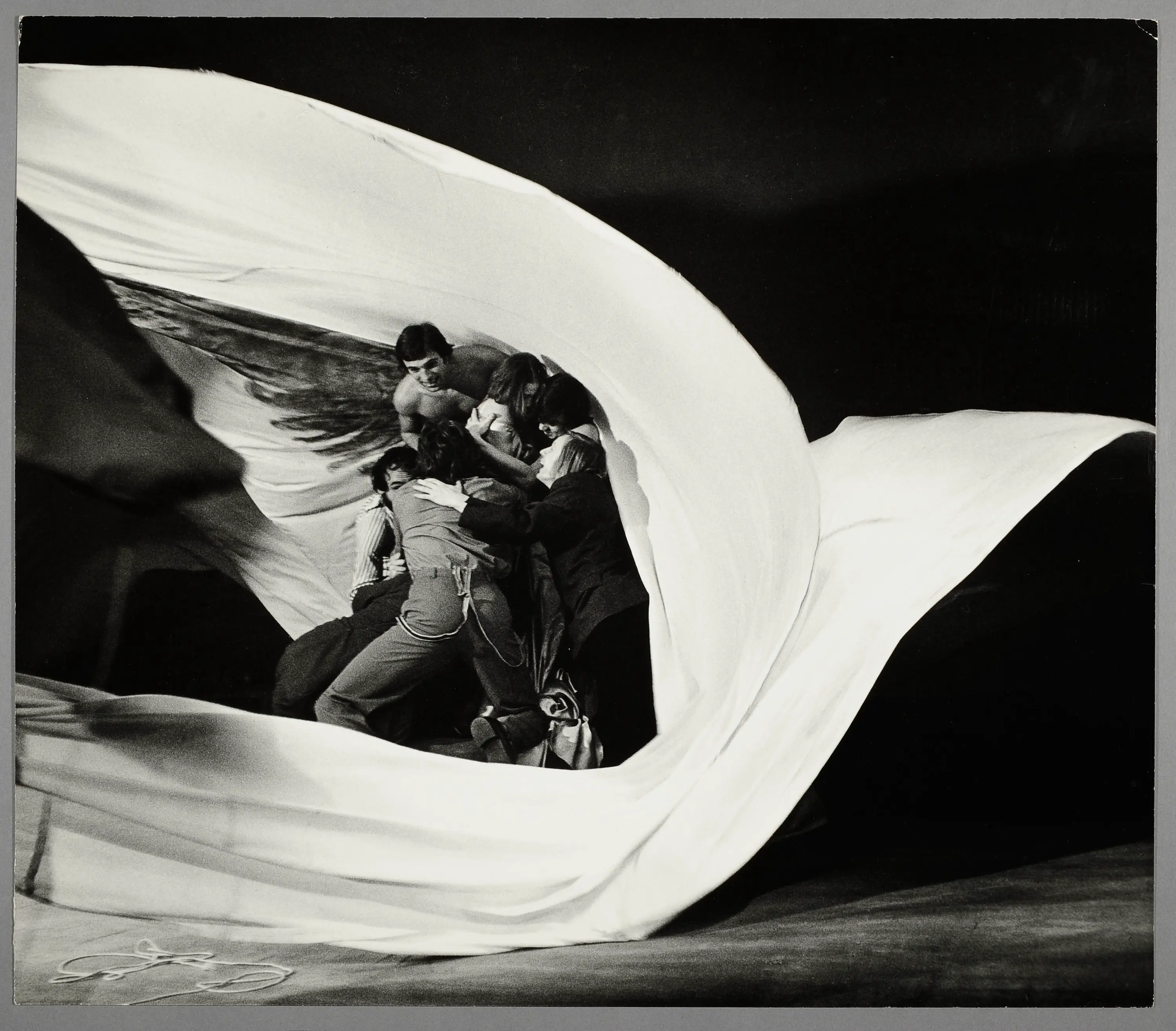

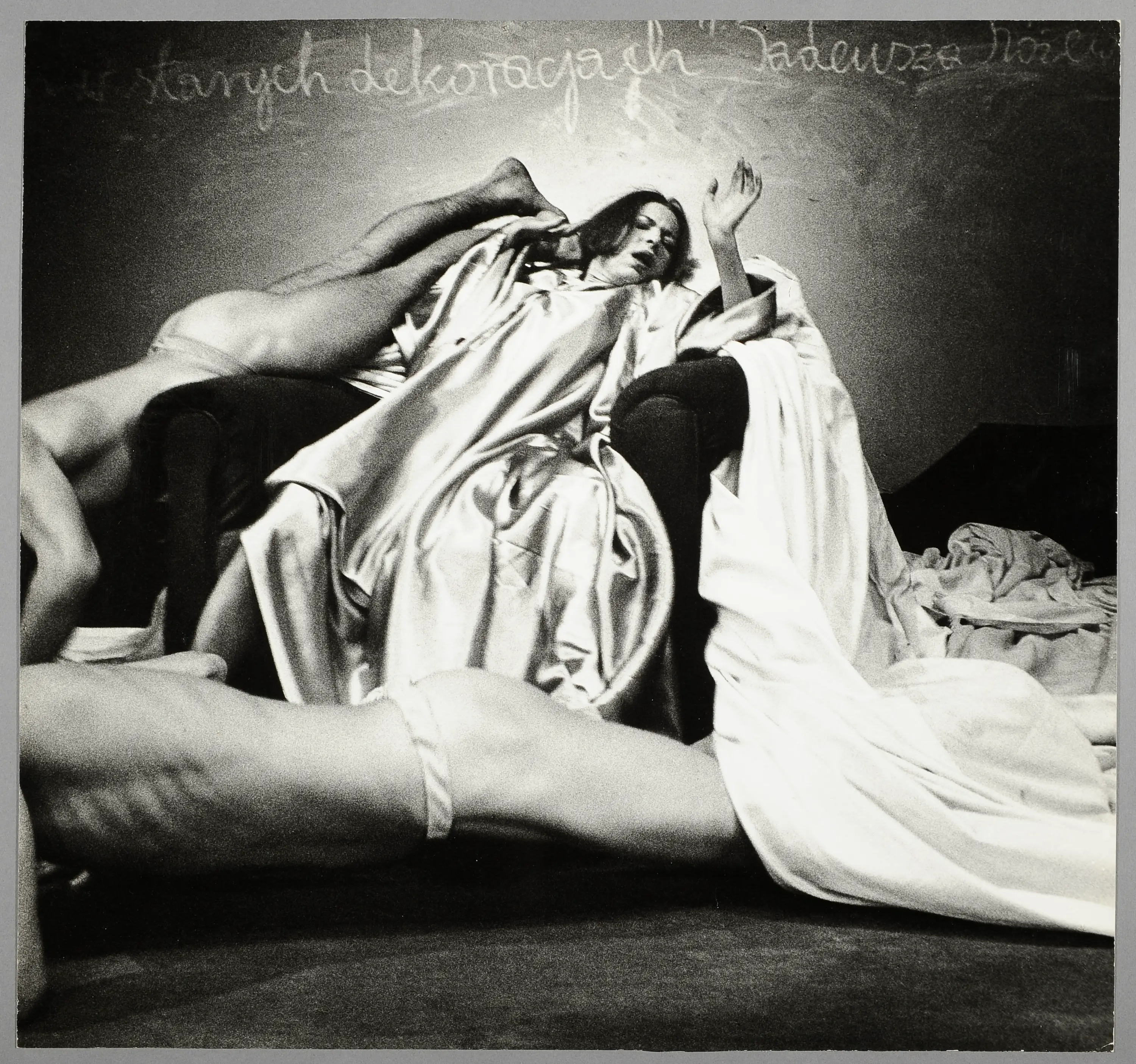

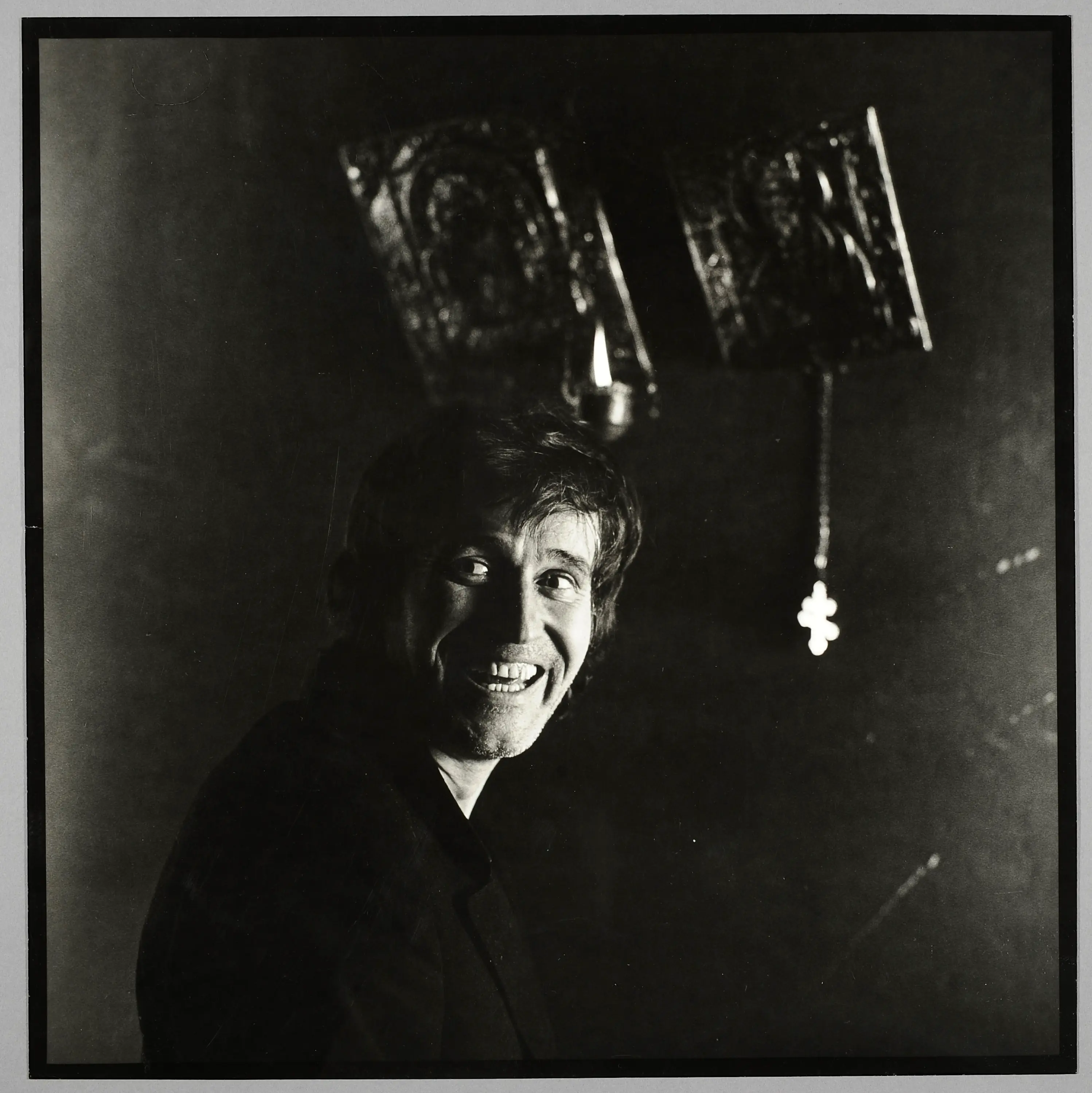

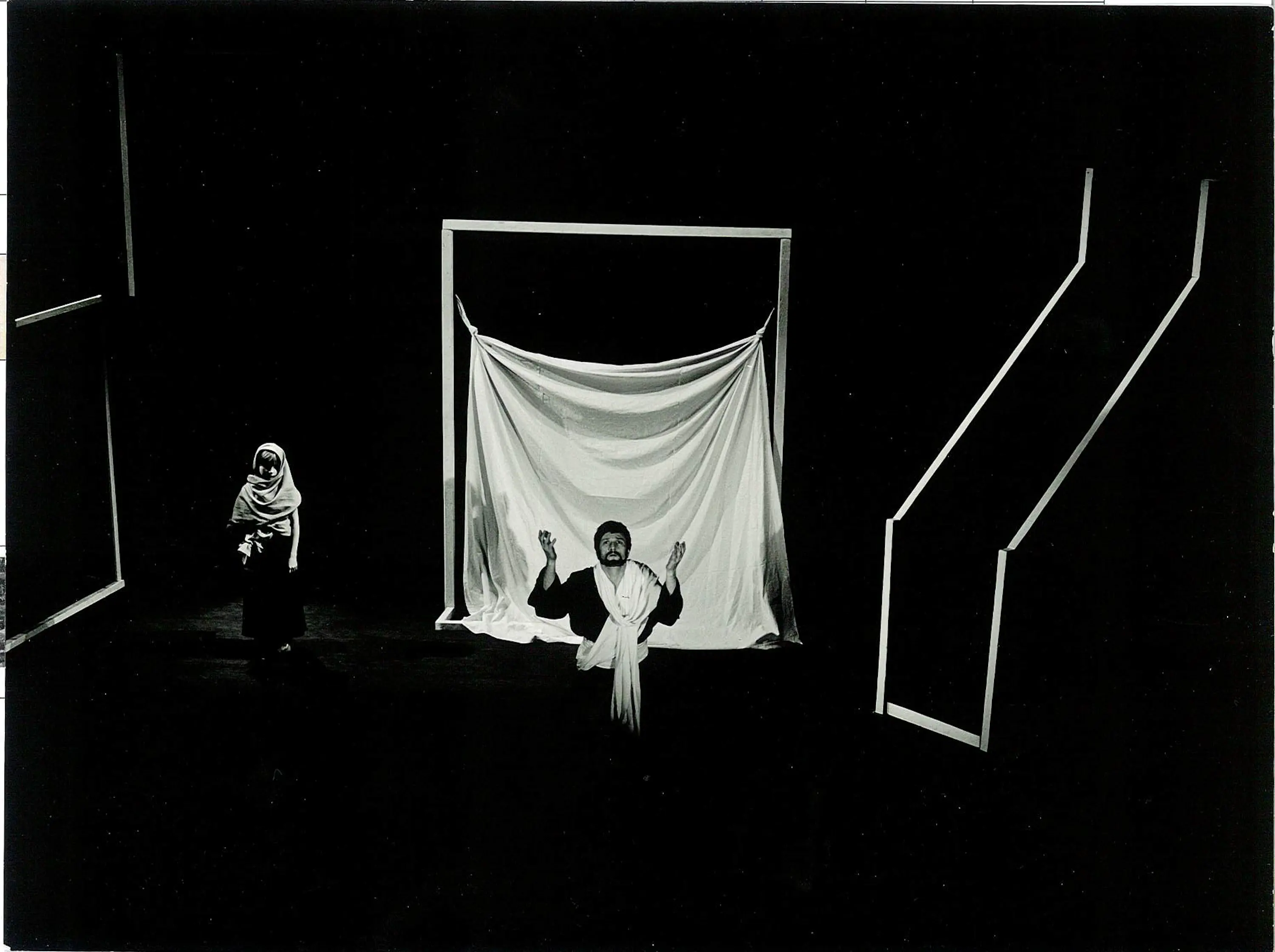

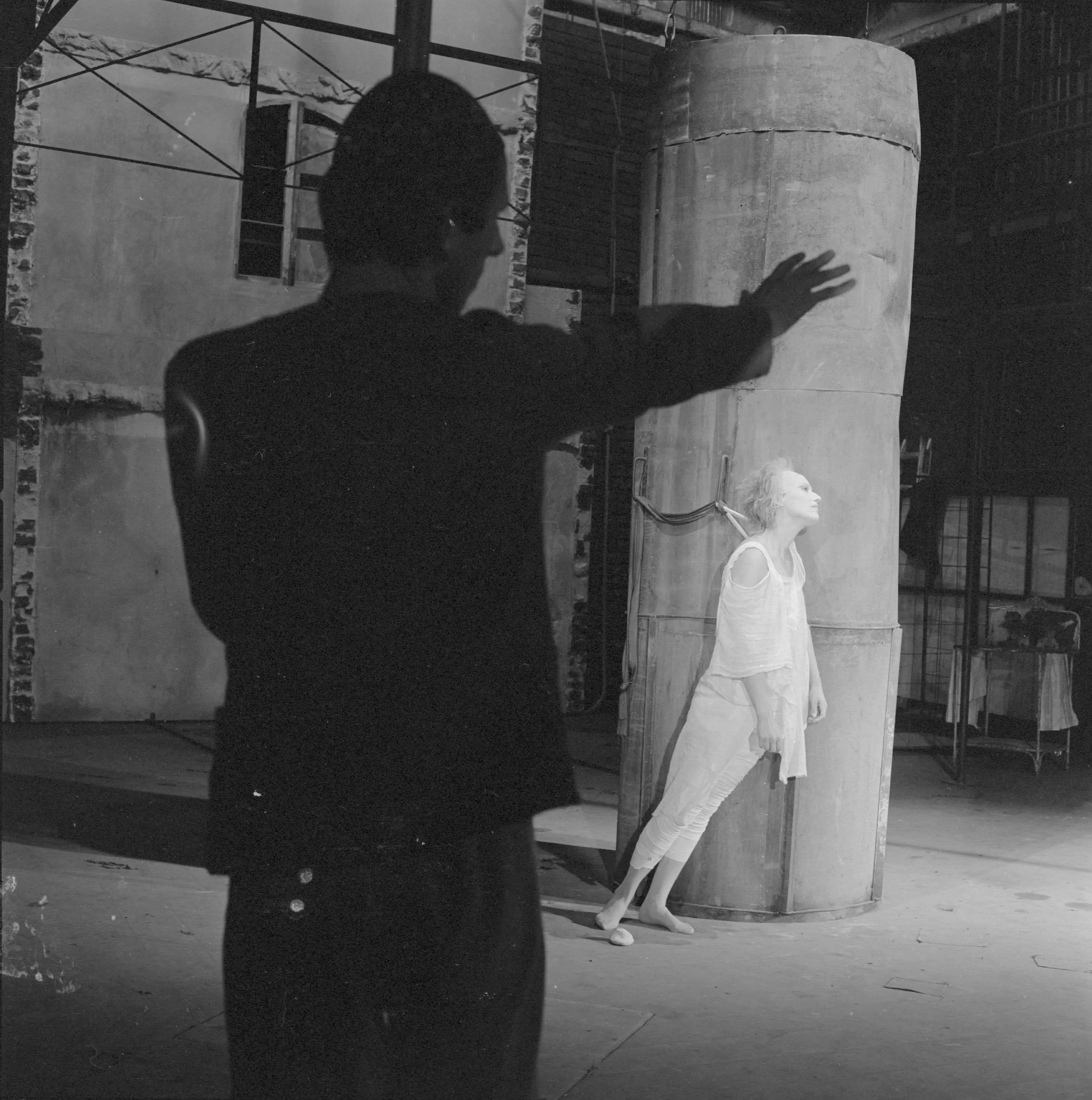

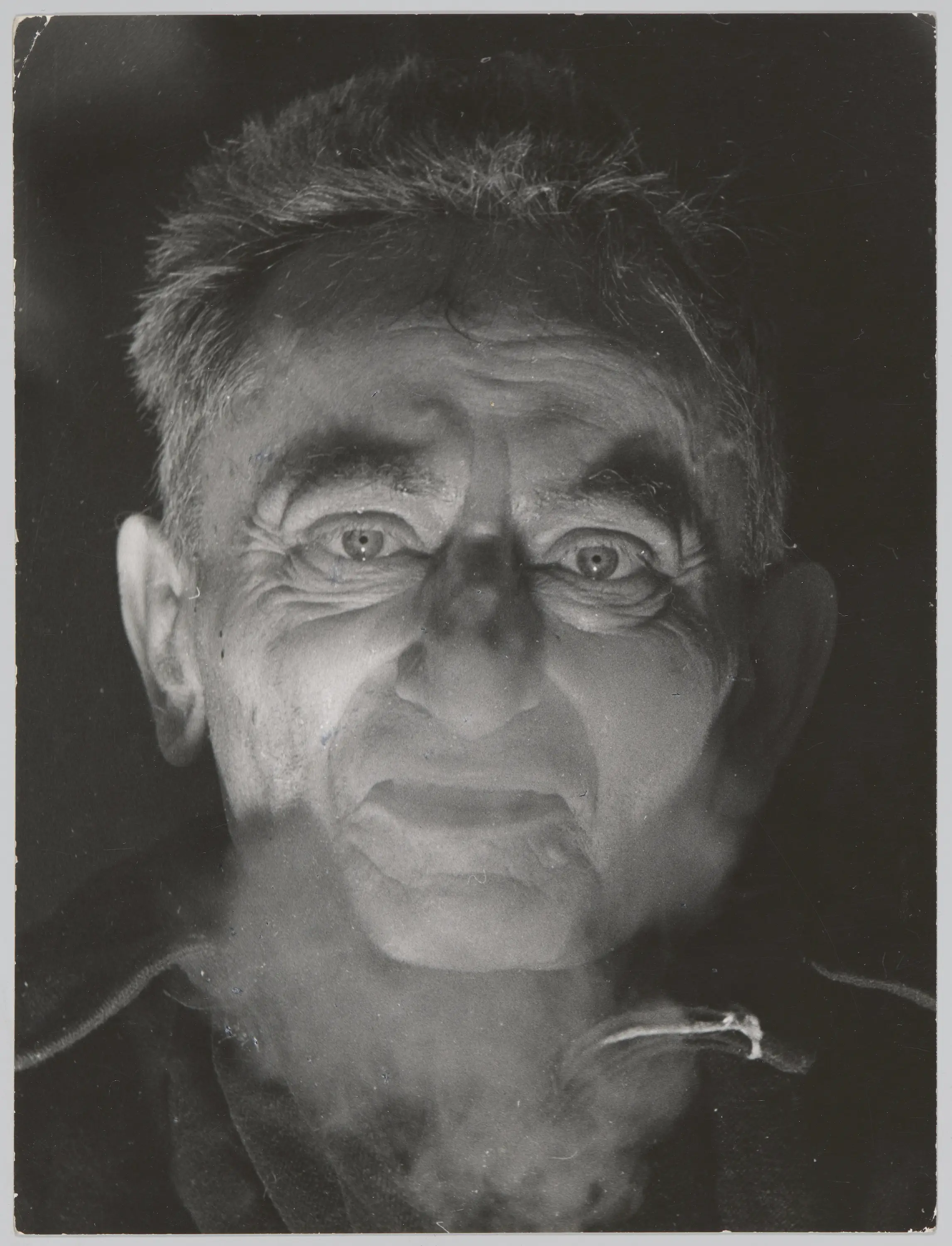

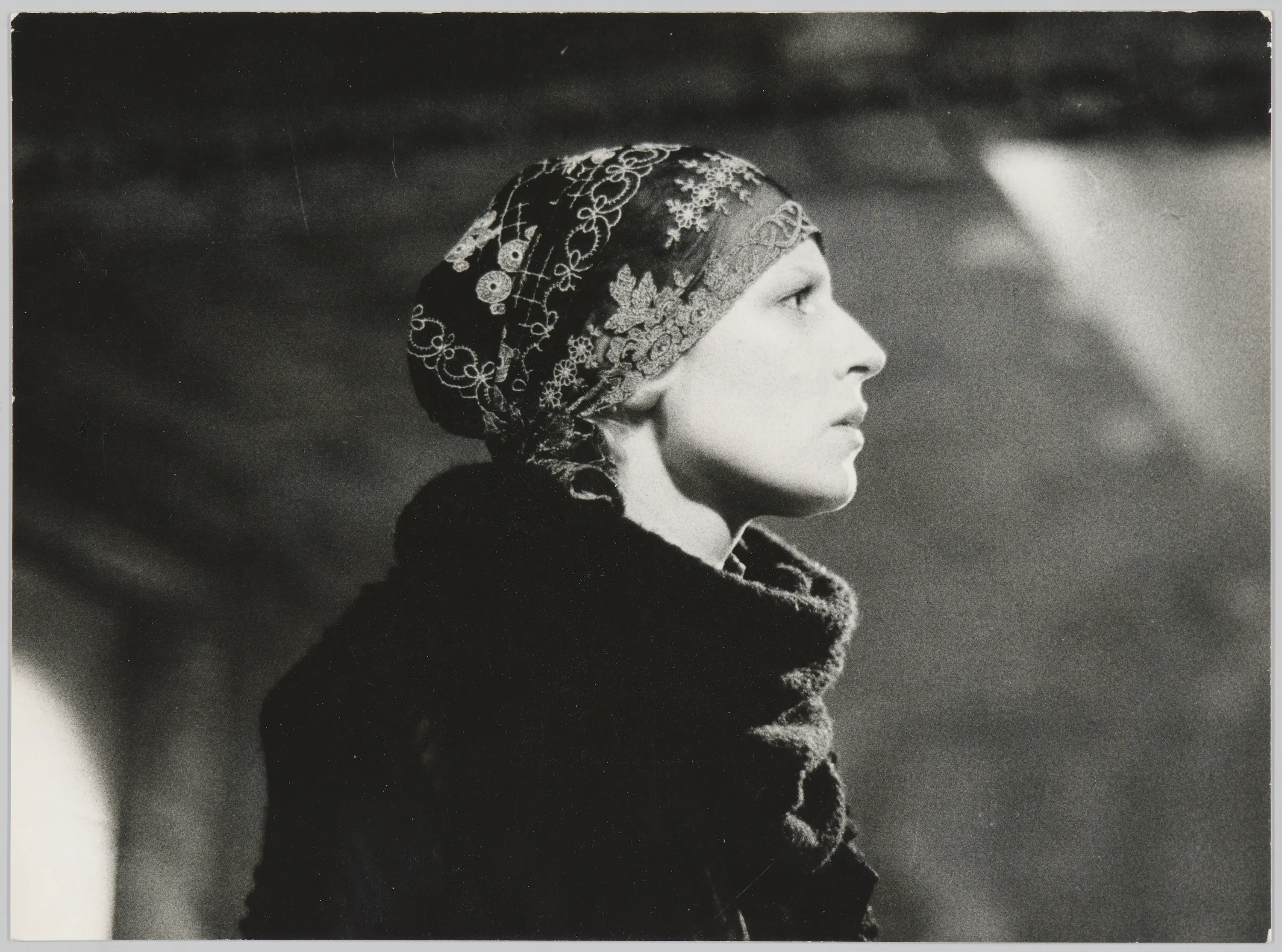

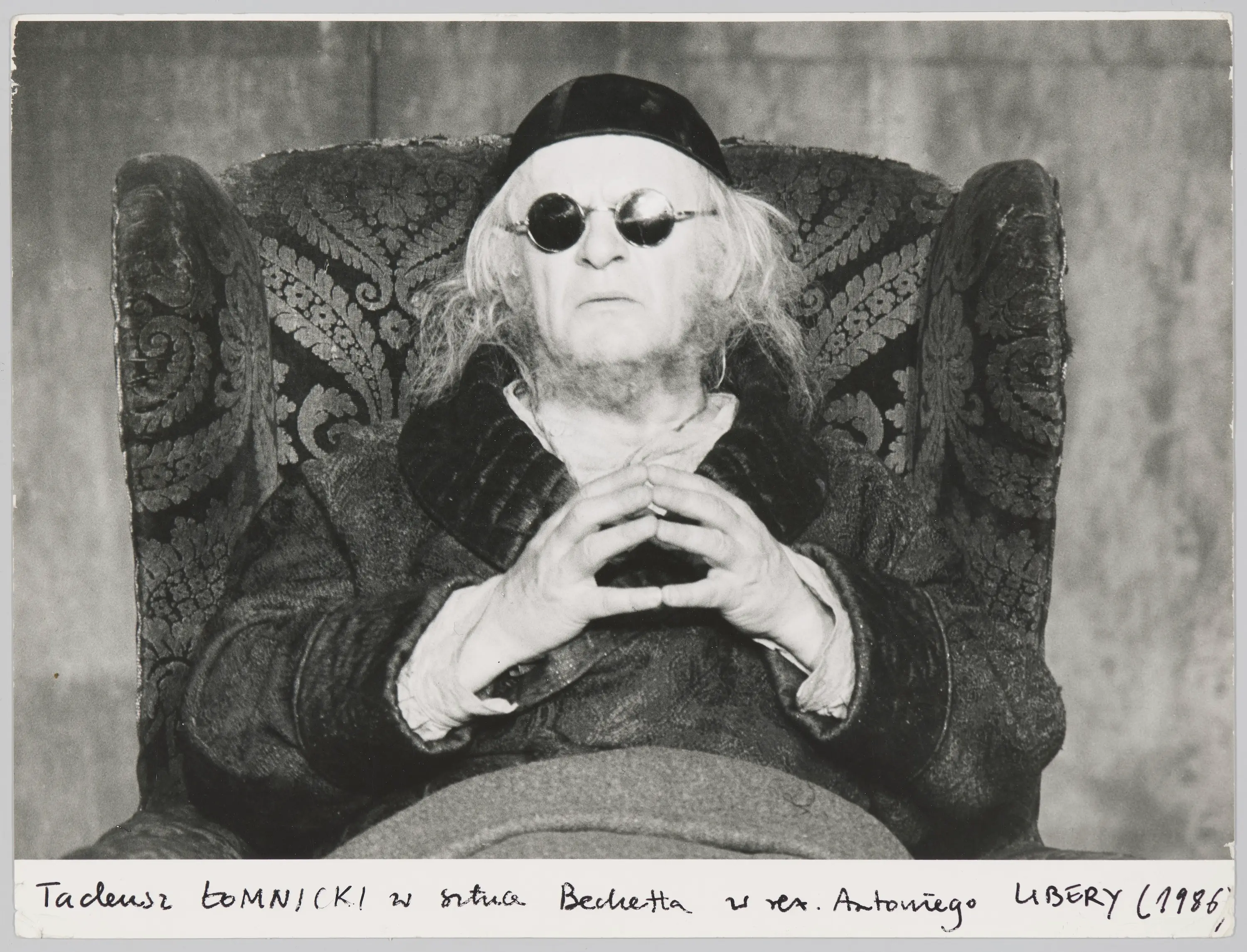

Theatre photography is also worth taking a closer look at because of the enormous effort that goes into creating a performance and the fact that not much is left of it afterwards. Luckily, sometimes performances are recorded on video, and in rare cases, the set, costumes and designs are not destroyed.

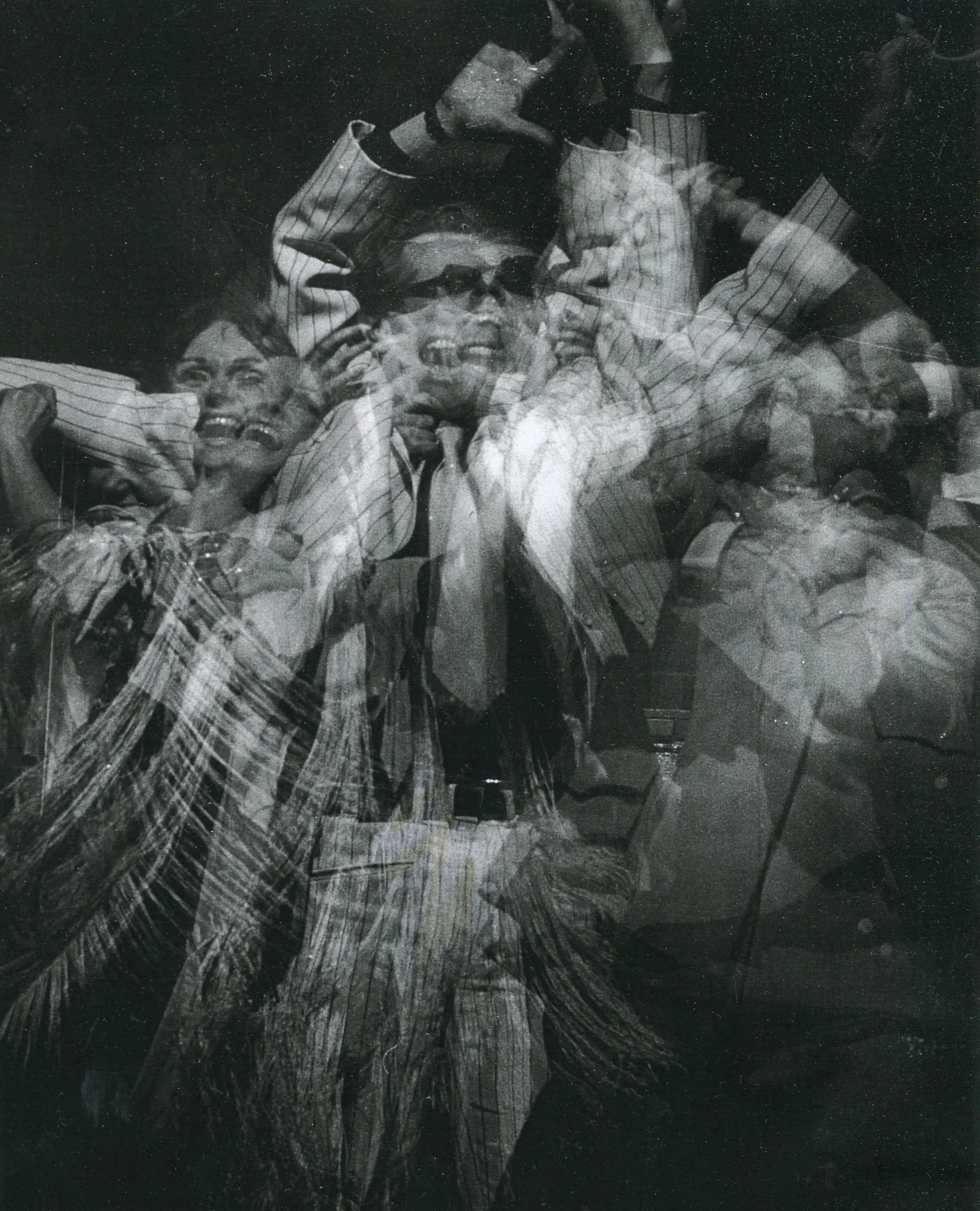

But nothing captures the performance as faithfully as the performance itself: it builds up with every clatter, every grunt of the actor, with every swirl of dust in the sheaf of theatrical lights. Nothing but the atmosphere of the theatre can do it justice. There is a misrepresentation and a sense of betrayal in any performance recording; when these misrepresentations are superimposed on the fluctuations of the audience's memory (each different), we get a panoply of disparate records. The medium that is probably closest to theatre and most faithful to it is photography. Hence the idea of devoting an exhibition to it.

Photography, like video, is a mechanical recording and a relatively faithful reflection of stage reality. It sequences theatrical material into frames and images similarly to human memory, which is why the associations are so close, and photography is read as a natural, unaltered record. It is true that it chooses the most convenient points of view (in space and time) and sometimes constructs points of view that are entirely new and independent of the viewer's memory (because, for various reasons, they are inaccessible to them), but, unlike video recordings, it does not create a separate narrative that is filmed simultaneously by several cameras.